27 October 2022 –

In its resolution 5/4 entitled “Follow-up to the Marrakech declaration on the prevention of corruption”, the Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) decided that the Open-ended Intergovernmental Working Group on the Prevention of Corruption should continue its work to advise and assist the Conference in the implementation of its mandate on the prevention of corruption. In that resolution, the Conference also decided that the Working Group should hold at least two meetings prior to the sixth session of the Conference and thus address, at its fifth meeting, among others, the topic on : (b) public sector legislative and administrative measures, including measures to enhance transparency in the funding of candidatures for elected public office and, where applicable, the funding of political parties (UNCAC articles 5 and 7). Yet, there is no consistent practice in this area, globally. While some countries adopt international standards to regulate and promote transparency of political finance, others do not.

The 4th Regional Meeting sought to share experiences on where there is transparency in political financing, why it is often not applied in practice, and what civil society can do to advocate for the implementation of Articles 5 and 7 of the UNCAC and other higher standards of transparency in political financing, bearing in mind that there will be at least 18 elections held in Africa in 2022. The meeting looked at the experiences in educating and advocating for principles that can guide States when regulating political parties, promoting a balance between public and private political party funding, looking at what would be moderate contributions as opposed to unduly large contributions, and allocating public funding in a manner that neither limits nor interferes with political party independence.

A Regional Perspective on Funding of Candidatures for Elected Public Office and the Funding of Political Parties

Mauritius

Mr. Rajen Bablee, Executive Director of Transparency International-Mauritius stated that Mauritius does not have a law regulating election finances. The country was recently on the European Union and the Financial Action Task Force blacklisting due to its failure to put in place frameworks to be compliant with the recommendations. TI-Mauritius, as an organization advocating for accountability and transparency, pushed for some major interventions, but to no avail. Recently, a police raid found large amounts of money in the former Prime Minister’s home, but he stated that it was from political donations. This shows that at times, political donations can be used to hide ill-gotten funds. Mr. Bablee decried opacity that not only exists in party finance, but also for beneficial owners.

Mr. Bablee highlighted that it is unfortunate that political parties in Mauritius manage to bypass rules on legitimate financing mechanisms, and most of the money lost or used in elections is not traceable. Under the current rules, there are not many suspicious transaction reports raised against political parties in Mauritius, while one can arguably observe suspicious ongoings in this regard in the country. The fact that almost all heads of institutions are president-appointed could be a contributory factor to the lack of accountability and transparency that exist. Mr. Bablee cautioned that the challenges begin with the Supreme law of the land, looking at how it allows for registration of parties to be done at any election phase including 2 weeks before candidate nomination. He argued that the definition of political parties is insufficient and only looks at it as an organization with a common purpose, while it clearly states in the constitution that it should be a lawful association.

On June 28, 2019, the Prime Minister of Mauritius proposed a political financing bill on political parties to prevent undue influence. The bill provided for the heads of institutions to be given powers to provide more monitoring of political party financing. However, in 2020 the bill was discarded. Section 41 of the Electoral Act mentions that the Electoral Commission should have the responsibility of oversight and registration of parties and candidates; nevertheless, nothing explicit has been prescribed so far. The maximum limit for donations to candidates is 300 000 rupees (approx. USD $6725) for individuals and 150 000 rupees (approx. USD $3362.50) for those in parties. It is common for spending amounts to be disclosed but the commission does not have the power to investigate these even if there are suspicions of overspending. There have also been allegations that those who speak up are targeted or blacklisted. The absence of a proper law on spending limits has gone counter to transparency and accountability and is contributing to a negative culture of opacity and impunity. CSOs have called on the private sector not to contribute to political parties, as a way of fighting unaccounted donations by the private interests; however, barely any have signed this pledge.

Grosso Modo, the absence of a law to regulate political parties, has generated a culture of impunity according to Mr Bablee. Promises that are made before elections about laws promoting transparency and accountability suddenly become empty. The murder of a political agent and the Covid-19 pandemic have shed some light on the unhealthy links between political parties and their agents. This is demonstrated by expenses made by politicians, their involvement in kickbacks, and flouting public procurement rules under the cloak of emergency situations during the pandemic.

Transparency Mauritius believes that it is time for Mauritius to apply meaningful changes: reforming the country’s politico-legal system is an uphill task which would demand full support from every citizen to be effective. It is therefore necessary for the population to be educated about its role, its powers, and its responsibilities.

Lesotho

Mr. Lerato Nkhetse, Executive Director of Migrant Workers Association and Ms. Mantopi Lebofa, Director of Technologies for Economic Development posited that in the country, registered political parties are entitled to funding from the Consolidated Fund for the purpose of campaigning and the payment of party agents in line with the provision of the Electoral Act, 2011 – Section 70(4) . Section 70 (5) provides that political parties which participated in the elections are entitled to funding from the Consolidated Fund on an annual basis depending on the number of seats it has in the National Assembly. The law also provides for private funding, campaign spending, ongoing party activities and sanctions provided for political finance infractions. Parties are permitted to receive funds from outside Lesotho for the conduction of election campaigns from any organization or person provided that funds over M200 000 (approx. USD $11 020) be disclosed to the IEC and that the funds be paid into the party’s declared campaign transaction bank account. However, there is no provision in the law requiring the IEC to publicly disclose the information on donations being reported to it.

Section 71 of the Act provides for expenses incurred in contesting elections, including the propagation of the political parties or candidates’ views and elector education. It also provides where funds may not be used, in instances such as personal expenditure not related to contesting elections. It is an offence to reward any elector to vote or to vote in a certain manner, and or use the funds to invest in any business or property directly or indirectly.

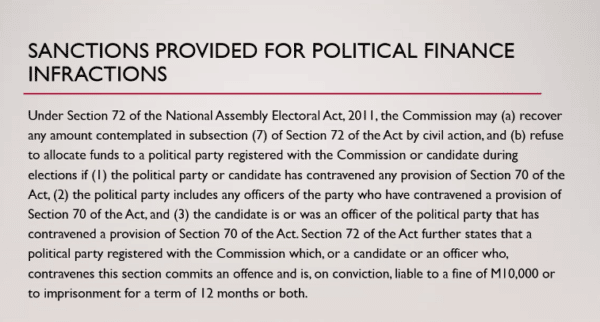

Under Section of the 72 Electoral Act, 2011, the Commission may recover any amount contemplated in subsection (7) of Section 72 of the Act by civil action. The Commission may also refuse to allocate funds to a political party registered with the Commission or candidate during elections if the political party or candidate have contravened any provision of Section 70 of the Act. Furthermore, the political party includes any officers of the party who have contravened a provision of Section 70 of the Act. Section 72 of the Act provides for sanctions for contraventions, stating that an offence and is, on conviction, liable to a fine of M10,000 (approx. USD $550) or to imprisonment for a term of 12 months or both.

Kenya

Ms. Harriet Wachira from Transparency International-Kenya pointed out that their work has focused on advocating for a legal framework to manage political financing. A struggle they have had for a long time has been getting a law on campaign financing which has never been fully implemented since 2013. This has included sharing memoranda with parliament and taking parliament to court, where they obtained a semi favorable ruling resulting in the body drafting appropriate legislations. Unfortunately, due to time constraints it was impossible to have the legal framework for campaign financing implemented for this year’s elections. As TI-Kenya, they have been pressing the Election Commission to monitor the use of public resources during campaigns, where they have been deficient. CSOs have therefore had to step in to complement that role and try to fill in gaps. In terms of data generation, in 2021, the Minister of the Foundation for Democracy sent surveys which attempted to determine the average sum a candidate needs to campaign, leading to the release of a report. When comparing the limit that the Foundation for Democracy had given, some discrepancies were observed. It is hoped that by the next elections in 2027, the law put in place will be implemented effectively.

On the question of limits on spending, TI-Kenya confirms that this must be implemented effectively, and that private contributions and their undue influence should be managed. There are allegations of tobacco businesses, for example, attempting to influence parliamentarians, so there are real risks of private interests impacting people’s lives. Interest groups have also managed to enter government to attempt to prevent limits on the use of plastic, for instance, which is why state resources should be used to prevent the extent to which private interests influence elected officials. This year’s election was an interesting experience where the incumbent and opposition both had access to government funds. Had this not been the case, the campaigns could have gone very differently as the public resources go a long way in funding associated costs of elections. One should remain aware, however, of the current risk of private funding overrunning public finance.

In summary, there should be restrictions on this government funding, particularly where state resources come straight from the Ministry of Finance. There must be transparency and accountability. For the longest time there have been requests to make the party’s budgets transparent, but to no avail. Spending limits have been debated in parliament to see how much money is usually spent in a campaign. Clear amounts were not reached but at least some guidelines have been set on cost items such as media and personnel, including limits on transportation, and determining liters of fuel used. Ms. Wachira forwarded some recommendations as such: creating a dedicated institution that monitors and tracks spending and donations of political parties and campaign periods; including sanctions to enable a party/independent sitting out and being banned from elections in an election cycle in cases of contraventions; banning cash donations of any amount; and enforcing infractions without going through courts.

To gain some insight from someone at the source, Ms. Florence Birya from the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties (ORPP) in Kenya provided participants with her perspective on the issue of political financing. The ORPP’s mandate, she states, is to register and manage the funding of political parties in Kenya. She confirmed that through the Ministry of Finance, 0.3 percent of whatever amount is allocated to the government budget is allocated to the political parties’ fund. Kenya had elections in 2022 with 6 elective positions at both regional and national levels. The office of the registrar has functions to administer and regulate the funds for political parties, although the regulation aspect is very broad: the life of a party begins at the point where a certificate of registration is given to a party, which is very important and so must be monitored to ensure accountability over its lifetime. Overall, the scope of the ORPP’s activities stretches as wide as auditing, capacity building, and working continuously with parties and their leadership.

The political parties in Kenya used to have more influence, partly because resources provided to the managing office were insufficient for it to do its work, but then a separate law was drafted with the electoral commission which provided autonomy to the office of the registrar and enabled them to focus on the registration and management aspects. This management is essential, as there is all the work during elections but there is also a continued influence of parties even after elections. In parliament there are majority and minority leaders, who implicitly are given party instructions which they follow, even as they provide oversight over the executive from parliament. Therefore, parties have influence on the political direction of the parliament, which is why the ORPP may need to consider regulating the influential reach of these parties in the National Assembly agenda. The ORPP has at times tried to respond to Members of Parliament’s misconducts and contacted the parties they belong to remedy and prevent any potential undue influence. This is still a work in progress.

Mrs Birya cautioned that the tendency is to look at the expenditure side of parties and not the member contributions. One may need to also look at this area because this is where illegal financing can come in, or overly large donations from potential businesses which are disguised as contributions, which can in turn influence the party. Therefore, it was established that individuals cannot contribute more than 5% over one year to one party’s finances to prevent them from capturing these parties. It was also established that foreign donors cannot support Kenyan political parties financially, that they can only provide technical support, and cannot provide physical property. Public financing of parties is targeted for specific expenses. This is supposed to help level out opportunities between parties of different sizes and different amounts of funding. Any party receiving this money, however, must be transparent and open a separate account for this purpose to be reported through audit. To ensure that Parties comply from an informed place, the ORPP trains political parties on the best and good practices expected for compliance.

Conclusions

In conclusion, political party financing laws or policies must at all cost demand for more transparency. Only when political parties or individual candidates are transparent about their source of funding can CSOs be able to scrutinize the motives of the financiers and the agenda they represent. CSOs can then raise public awareness of that party or candidate and of the interests of the people or businesses behind such a campaign.

In Nigeria for example, CSOs recognized the challenges the electoral bodies were encountering to enforce transparency rules regarding the electoral process. Nigerian CSOs therefore developed a methodology to demand transparency from the aspirants and are presenting their findings on this portal. Currently, candidates have been sent a questionnaire regarding the disclosure of their electoral financing methods to improve their integrity. Some are giving feedback which is recorded and continually updated to indicate those that have decided to voluntarily disclose.

UNCAC Coalition tools to make the UNCAC Implementation Review Process more transparent and inclusive

Beyond the conversation about political finance, Danella Newman from the UNCAC Coalition also provided a panorama of the panoply of tools that the UNCAC Coalition has developed to make the UNCAC Implementation Review Process more transparent and inclusive to civil society organizations and citizens.

1. UNCAC Review Status Tracker

– an easy-to-use tool that permits users to access up-to-date information about the review status of all States Parties to the Convention. It goes further, by also including information about which States Parties have signed the Transparency Pledge and, importantly, if they are compliant to it, if the focal point for the country review is known, and if a parallel report has been produced for this country.

• This tool is particularly relevant in the region, as 32 review processes are currently ongoing in Sub-Saharan Africa.

• Check your country’s review status and get involved!

2. Transparency Pledge

– a commitment to be signed by States Parties to the UNCAC to uphold six principles aimed to make the review process more transparent and participative.

• Of the 33 signatory States, only 1 (Mauritius) is from the region.

• Check the UNCAC Review Status tracker to see if they are complying with it and hold them accountable. If your country has not signed the Pledge yet, but its 2nd cycle review is ongoing, then advocate for them to sign it and get involved in the review process.

3. Guide to Transparency and Participation in the UNCAC Implementation Review Mechanism

– a road map for both States and civil society highlighting best practice examples of transparency and civil society participation at different stages of the UNCAC review process.

4. Access to Information Campaign

– a campaign for more accountability and transparency in the UNCAC review mechanism, where CSOs around the world use the Coalition’s ATI template to request essential information and documents on both the 1st and 2nd UNCAC review cycles and track levels of transparency and compliance with ATI legislation globally.

• only six countries from the region have participated in the campaign (Benin, Botswana, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia and Mali) with only one case (Benin) providing satisfactory results. Any civil society organization or anti-corruption activist can join the campaign. Write to email hidden; JavaScript is required to express your interest in participating!

5. Civil Society Parallel Reports

– the Coalition support CSOs from ODA-recipient countries in producing parallel reports on the implementation of Chapters II and V of the UNCAC to look at the implementation of the Convention’s provisions in practice.

• In Sub-Saharan Africa, there are published parallel reports from CSOs from the following countries: Zimbabwe, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Togo, Uganda, Ghana, Benin, The Gambia, Madagascar, and Zambia. CSOs are currently writing parallel reports on: Namibia, Chad, Ethiopia, and Burundi.

• The call for applications for support to write a parallel report is currently closed but will likely reopen soon.

Additionally, the UNCAC Coalition is carrying out comparative research to look at the good practices and lessons learned from other anti-corruption monitoring mechanisms that could inform our efforts to strengthen the UNCAC’s Implementation Review Mechanism (IRM).

If you have experience working on anti-corruption monitoring mechanisms that could be useful to inform this research or you would like to learn more, please get in touch with Corinna Gilfillan, email hidden; JavaScript is required.