30 May 2022 –

Which countries’ whistleblower protection laws are considered a best practice? What gaps in the existing legal framework prevent the effective protection of those reporting on corruption? And what actions are needed to improve the situation in the MENA region? These questions were the focus of the discussion during the fifth meeting of the UNCAC Coalition’s MENA regional group held on May 9, 2022. The discussion was led by global experts from the Government Accountability Project (GAP), Tom Devine (Legal Director), and Samantha Feinstein (Staff Attorney and Director of the International Program), who also serves as the Coalition Coordination Committee’s (CCC) Vice-Chair.

The meeting was opened by the MENA’s CCC representative, Aya Riahi, from I Watch. Denyse Degiorgio, representing the Vienna Hub, provided updates, including progress on ongoing campaigns such as the ATI campaign and the status of preparations for the UNCAC Implementation Review Group (IRG) 13th session.

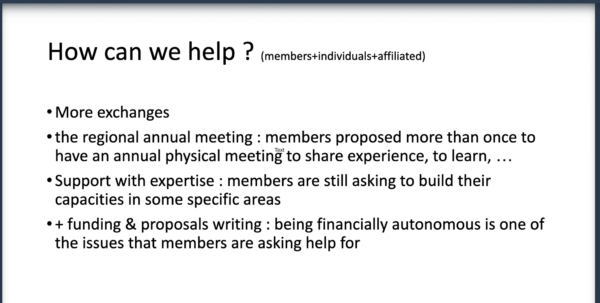

MENA regional coordinator, Karim Belhaj Aissa, presented the results of the Coalition annual survey conducted among its members to evaluate the program of activities in 2021 and identify their needs and aspirations for 2022.

Are whistleblowing laws working?

The second part of the meeting was devoted to the subject of whistleblower protection, where GAP experts provided a global overview of whistleblower protection legal frameworks and their evolution over the years. Four decades ago, only one country had a whistleblower law (the US). Currently, 46 countries have whistleblower statutes, including the European Union’s whistleblower directive in place since 2019. Intergovernmental organizations have whistleblower policies, including various United Nations bodies and most development banks, including the Islamic Development Bank and the African Development Bank. However, both experts emphasized that laws differentiate in the quality of the controls put in place to guarantee the effectiveness of the protection provided to whistleblowers.

Best practices and comparative experiences in this area are the best references for law-making. Such best practices include, among others:

- Making sure the right to freedom of expression is not violated and guaranteed in practice.

- The dedicated law should protect against any abuse of power.

- The right to refuse to break the law should be protected, meaning that one can refuse to participate in illegality and has rights against retaliation.

- The law protects against direct as well as indirect retaliation.

Many whistleblower laws simply protect the whistleblower from harassment in the workplace, such as from being fired, reassigned, or demoted. But “harassment” might go way beyond. Anything that might act as a deterrent must be illegal under whistleblower law, whether it is firing the worker, using violence, seizing the worker’s property, suing for damages in tort, or filing criminal charges against the reporting worker. Prosecutions take years in almost all countries. During those years, interim measures should be provided if there is credible evidence that retaliation may have occurred. Otherwise, it might be the case that at the end of those 5 to 10 years (or even more than 10 years in the case of the US), it may not matter anymore as the reporting person might have already lost her/his job, possibly going bankrupt, irrevocably ruining one’s reputation, career or family.

The situation in the MENA region

Countries in the region need to develop proper whistleblower protection laws, as most countries still do not have such legal frameworks in place. The key is to enact laws that offer adequate protection. During the exchange of views that followed GAP’s presentation, it was highlighted that the absence of whistleblower protection laws in MENA has potential for impactful civil society advocacy. Advocating for a law that meets international standards and best practices from the onset may yield more results than calling for amendments to a flawed whistleblower protection law.

One participant highlighted that in his country, the right to freedom of expression is clearly violated, and heavy restrictions are put on the reporting of corruption, including by the media. He said that whistleblowers are known to be persecuted for exposing governmental corruption, which reinforces the secrecy around public sector wrongdoings.

Another issue discussed was the possible exposure of information on whistleblowers in Tunisia since the Tunisian president shut down the Anti-Corruption Authority more than a year ago. The authority dealt with whistleblower protection in general and issued protection decisions to those concerned. Since its closure, activists in the country, including Coalition member I Watch, have been raising serious concerns regarding the risk of exposure of Tunisian whistleblowers’ identity, which constitutes a risk to their physical integrity.