What is asset recovery?

Asset recovery – as outlined in the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC chapter V) – refers to the process by which the proceeds of corruption transferred abroad are recovered and repatriated to the country from which they were taken or to their rightful owners.

A precise account of the proceeds of corruption circulating the globe is not possible, but the World Bank estimates that developing countries lose US$20-40 billion each year due to corruption. This money could be spent on tackling poverty, providing decent public services and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

This significant injustice often occurs ostentatiously and in plain sight, but due to legal and institutional complexities and lack of cooperation between states it is all too easy for the corrupt to hold on to their ill-gotten gains.

With only US$1.398 billion assets frozen and US$147.2 million returned by OECD countries between 2010 and 2012, there is a huge gap between what goes missing and what is recovered and ultimately returned. We need concerted global efforts to improve asset recovery systems and increase cooperation and coordination between jurisdictions.

The UNCAC Review Mechanism’s focus on asset recovery in its second cycle of reviews (2015-2020) is an ideal opportunity for civil society to work with governments and advocate for fair and effective asset recovery: a process that not only punishes corrupt agents by confiscating the proceeds of corruption, but transparently and accountably returns assets to the states from which they originally came.

Obstacles to asset recovery

The World Bank has grouped the obstacles to asset recovery under three headings:

- General barriers and institutional issues: lack of political will to identify asset recovery as a priority and failure to attend to anti-money laundering measures to prevent asset flight.

- Legal barriers and requirements that delay assistance: onerous requirements for mutual legal assistance, banking secrecy, lack of non-conviction based recovery procedures and restrictive evidentiary and procedural legislation.

- Operational barriers and communication issues: difficulty identifying contact points in other countries and delays in processing mutual legal assistance requests or poorly drafted requests.

UNCAC and asset recovery

In the UNCAC chapter V (Articles 51-59) is devoted to asset recovery.

Direct recovery of assets

UNCAC (Article 53) provides for direct recovery of assets, whereby a foreign state is able to initiate a civil action in a foreign jurisdiction to establish title and ownership of property. It also means that courts should be able to order compensation or damages to a foreign state and recognise them as legitimate owners of property.

In the case of direct recovery of assets through the use of civil proceedings (Article 53), the defrauded state, represented by counsel, will stand – like any ordinary private plaintiff would do – before the foreign jurisdiction(s) where proceeds of corruption are located and will claim their repatriation to its national treasury. The legal basis for such civil claims are twofold:

- Ownership claims: The UNCAC requires States Parties to take necessary measures to allow other states to initiate a civil action in its courts (Article 53.a)) and intervene as a third party in a confiscation procedure (Article 53.c)) for the purpose of establishing its prior title or ownership over proceeds of corruption.

- Claim for damages: The UNCAC further requires States Parties to take necessary measures to allow other states to stand before their courts and seek compensation or damages for the harm caused by the commission of a corruption offence (Article 53.b); see also Article 35 on “compensation for damage”). This innovative provision departs from the idea that proceeds of corruption should be recovered only on ownership grounds and aims to provide a concrete remedy to states harmed by corruption in situations – such as bribery or trading in influence – where the proceeds of corruption involve funds of private origin to which the state was never entitled. Under this scheme, no public money was ever involved; therefore proceeds of corruption are not returned because they belong to the defrauded state but because it suffered damage as a result of the commission of the underlying corruption offence.

In both cases, once ownership or damage is established, no further step is required to provide the basis for repatriation of those ill-gotten gains to the defrauded state.

Asset recovery and foreign bribery: Making the connection

Asset recovery is not only about recovering stolen/embezzled public funds stashed away by corrupt agents or confiscating the lavish properties they illicitly acquired abroad. The process involves any proceeds of corruption transferred abroad including those of private origin such as the illicit profits, benefits or advantages of monetary value gained by companies as a result of paying a bribe to a foreign official.

UNCAC Article 53.b) – which provides for direct recovery of property through compensation claims – was precisely established to provide a concrete remedy to states harmed by corruption in situations – such as bribery or trading in influence – where the proceeds of corruption involve funds of private origin to which the state was never entitled. And yet, as a Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative (StAR) report shows this provision has yet to be implemented. In the majority of foreign bribery cases settled abroad, victim countries are left out of the bargain. This is all the more unfortunate given the heavy and increasing reliance on negotiated settlements or out-of-court resolutions in both common law and civil law jurisdictions. However, it is believed to be equally true when it comes to ordinary court proceedings.

International cooperation for confiscation (Articles 54 and 55) and return (Article 57) of proceeds of corruption

Also known as forfeiture, confiscation consists in “the permanent deprivation of assets by order of a court or other competent authority” (UNCAC, Article 2). It is a powerful legal weapon to deprive corrupt agents from their ill-gotten gains.

Confiscation actions can be brought either domestically in the victim country or in the recipient countries, where proceeds of corruption are located. Either way, once a confiscation order is made, assets are not directly repatriated to the victim country.

According to UNCAC Article 57, the return of the assets will be organized as follows:

- When confiscation is ordered in the victim country, the return of assets requires a request from the victim country (requesting party) to the recipient country (requested party) Upon such a request, the requested party is obliged to return the confiscated property to the requesting party whenever said property is the proceeds of embezzlement of public funds or laundering of such funds (Article 57.3.a)); or when the requesting party establishes prior ownership over confiscated property or when the requested party recognizes damage to the requesting State Party (Article 57.3b))

- When confiscation is ordered in the recipient country, assets may be returned to the victim country either:

- directly through the order of a court in line with Article 53.c);

- through ad hoc asset sharing agreements in line with Article 57.5;

Stages in the confiscation and return process

There are three main stages: identifying and tracing assets; freezing and confiscating assets; and recovering and returning assets.

Identifying and tracing assets

Identifying assets is not as simple as following the money flow from bribes, embezzlement or other diversions of public funds. It is necessary to prove that the assets were unlawfully acquired.

Tracing assets means conducting investigations that follow the assets in order to establish the paper trail and to prove the assets were unlawfully acquired. This requires “resources, expertise and … effective international cooperation”. The FATF recommends implementing strong legal frameworks, minimising structural impediments through coordination, communication and resourcing, streamlining procedures and addressing cultural issues.

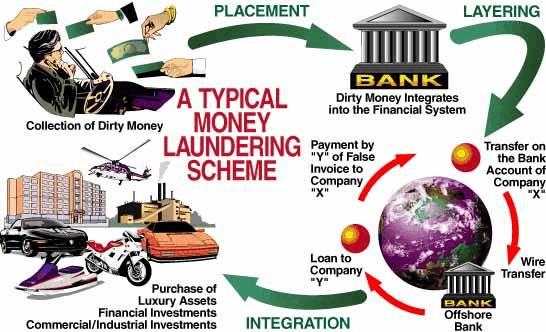

Money laundering disguises or mingles ill-gotten assets with legitimate funds or assets to hide their origin, which makes them all the more difficult to locate. This is enabled by certain financial centres, in which financial services providers (or “gatekeepers”) help conceal the proceeds of unlawful activities.

The international Anti-Money Laundering (AML) framework includes due diligence requirements for gatekeepers and institutions, including non-financial professions that might handle the proceeds of crime, such as law firms.

All these processes need constant updating to remain steps ahead of technological advances that give greater mobility to wealth and the possibilities for hiding and disguising it; with a mouse click the proceeds of corruption can easily be shifted to off-shore accounts, laundered and then moved again, mingling with legitimate funds and disappearing from view.

Freezing and confiscating assets

Freezing and confiscating the proceeds of corruption stops the assets from being used for further criminal activity.

The OECD defines confiscation as “the permanent deprivation of assets by order of a court or other competent authority”. The confiscation can follow a criminal conviction by a court or be non-conviction based, or administrative.

Non-conviction based asset forfeiture is essential to deal with cases where “the violator is dead, has fled the jurisdiction, is immune from investigation or prosecution, or is essentially too powerful to prosecute”. However, not all countries have this legislation in place and so have no recourse when faced with cases that cannot be prosecuted through the criminal courts.

Assets can be confiscated in two ways: property-based confiscation, which requires the identification of a particular asset; or value-based, which is based on the monetary value of assets that cannot be materially recovered, because for example they have been moved on or destroyed.

The FATF provides useful guidance for countries on the best practice in confiscation, including ensuring that the state has a legal framework to respond to requests to “identify, freeze and seize property”.

Recovering and returning assets

Once corrupt assets have been identified and legally confiscated they must be returned to their “prior legitimate owners” (UNCAC, Article 57). This final step in the asset recovery process can be complex, as it entails considering how to ensure the process is both transparent and accountable.

The whole asset recovery process relies mainly on effective cooperation between jurisdictions. Mutual legal assistance is covered in UNCAC (Articles 46; 54-57), and states are required to “afford one another the widest measure of legal mutual assistance in investigations, prosecutions and judicial proceedings”.

The StAR Initiative has useful recommendations on these considerations, in particular on the selection of appropriate financial management arrangements, the importance of on going monitoring to ensure funds are not re-appropriated and the role of civil society in this monitoring process.

Progress

Although some progress has been made in recent years, there is still a long way to go before asset recovery processes deter corrupt activity and provide remedies.

In 2014, the OECD found that its members had made little progress – with advances being made in only a handful of countries, leaving much room for improvement.

However, international efforts are beginning to bear fruit:

- With the UNCAC Review Mechanism, all States Parties are being assessed on their asset recovery legislation and processes with the aim of completing the reviews by 2020. This is opening up discussions and adding to our understanding as well as building on the potential for greater international cooperation.

- The Lausanne Process has held regular seminars on asset recovery since 2001 and is due to produce a comprehensive step-by-step guide on asset recovery, produced by practitioners from around the globe.

- In Addis Ababa in February 2017, 36 countries and international organisations came together to discuss the management and disposal of returned stolen assets – the last phase of asset recovery, which seeks to ensure returned assets are accountable and well used. The UNCAC Coalition submitted a letter to the meeting, proposing principles of accountable asset return. Further details on the topics and outcomes of this event can be found in the concept paper and the final report. The most recent expert meeting of this kind was held in Addis Ababa in May 2019.

- In 2010, the US Department of Justice launched the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative “aimed at combating large-scale foreign official corruption and recovering public funds for their intended – and proper – use: for the people of our nations.”

A few prominent successful international asset recovery cases:

- In the past 21 years, the Philippines has recovered more than US$1 billion of money, mostly from Switzerland, stolen by Ferdinand Marcos.

- By 2007, Peru had recovered over US$174 million, from jurisdictions such as Switzerland, Cayman Islands and the United States, stolen by Vladimiro Montesinos.

- To date, US$700 million of money stolen by Sani Abacha, has been frozen and forfeited by Swiss authorities and has been returned to Nigeria.

- In 2006 and 2007, British and South African authorities helped Nigeria recover US$17.7 million of the illicit gains obtained by Diepreye Alamieyeseigha, governor of the oil-rich Bayelsa state.

Source: StAR

There have been many failures too as with Jean-Claude Duvalier, Mobutu Sese Seko Suharto and Slobodan Milosevic to name just a few.

The Global Forum on Asset Recovery

The first Global Forum on Asset Recovery (GFAR) was held in Washington, DC, 4-6 December 2017, hosted by the United Kingdom and the United States with support from the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR). The meeting focused on assistance to four priority countries: Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Ukraine. GFAR was established as an outcome of the 2016 Anti-Corruption Summit, hosted by the United Kingdom. The results of the GFAR (such as an MoU between Nigeria, Switzerland and the World Bank which sets out the return of $321m of recovered assets) were concluded in the final communique.

GFAR Principles

The Principles for Disposition and Transfer of Confiscated Stolen Assets in Corruption Cases were agreed at the first GFAR in 2017.

- Principle 1: Partnership

- Principle 2: Mutual Interests

- Principle 3: Early Dialogue

- Principle 4: Transparency and Accountability

- Principle 5: Beneficiaries

- Principle 6: Strengthening Anti-Corruption and Development

- Principle 7: Case-Specific Treatment

- Principle 8: Consider Using an Agreement under UNCAC Article 57(5)

- Principle 9: Preclusion of Benefit to Offenders

- Principle 10: Inclusion of Non-Government Stakeholders

Civil society country reports

As a contribution to the GFAR, the UNCAC Coalition supported civil society organisations in preparing country studies on the four focus countries as well as a number of destination countries. The CSOs also prepared one-page summaries of the reports. Following up on those baseline reports, in 2019, Transparency International National Chapters prepared six GFAR progress reports looking at developments in France, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Ukraine and the United Kingdom. Links to those reports can be found in the fourth column of the table below.

| Country | Full report 2017 | Summary 2017 | Follow-up 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | Full Report | Summary | Follow-up |

| Nigeria | Full Report | Summary | Follow-up |

| Sri Lanka | Full Report | Summary | Follow-up |

| Tunisia | Summary | Follow-up | |

| Ukraine | Full Report | Summary | Follow-up |

| United Kingdom | Full Report | Summary | Follow-up |

| United States | Full Report |

The UNCAC Coalition also submitted a statement at the start of GFAR, delivered a statement at the closing plenary and issued a press release at the conclusion of the forum. It also co-organised the separate GFAR civil society agenda.

At the 8th session of the UNCAC Conference of States Parties in December 2019, Transparency International submitted a statement entitled: Calling for Transparent and Accountable Asset Recovery – TI Country Reports.

What to do about asset recovery?

Asset recovery is often perceived as a distant and technical process – the realm of international institutions and lawyers – far removed from the everyday concerns of civil society and the public more broadly. However, while it is a complex global phenomenon, it is also a local activity and has very real effects on the lives of people and prosperity of communities around the world.

Governments

Governments have a long way to go to ensure the comprehensive implementation of UNCAC chapter V on asset recovery. In 2015, the UNCAC Coalition noted changes that were needed including:

- Comprehensive implementation of chapter V by enhancing the confiscation of the proceeds of active bribery; and providing for the direct recovery of property through compensation claims.

- Effective implementation of chapter V by enhancing the direct recovery of property; and ensuring proactive enforcement action against corrupt officials and effective recovery of their ill-gotten gains through addressing political interference in the criminal justice system, immunity and grand corruption.

- Transparent and accountable implementation of chapter V by considering the use and management of the returned assets; and collecting and disseminating data on asset recovery.

Civil society

The UNCAC Review Mechanism’s focus on asset recovery in its second cycle provides an entry point for civil society organisations to get involved in asset recovery at the national level. There are many ways for civil society to get involved, including:

- Research and awareness raising on the impacts of corruption and the benefits of asset recovery

- Advocacy with national governments to ensure they implement the provisions in chapter V of the UNCAC

- Legal case work and analysis of on-going cases and asset recovery processes

- Monitoring the processes for the return of assets

The UNCAC Coalition is focusing on asset recovery as one of its advocacy priorities.

We are calling for the removal of barriers that prevent national treasuries from recovering corruptly-acquired assets stolen assets, establishing standards for transparent and accountable asset return and enabling civil society participation in the process.

The UNCAC Coalition submitted a statement on asset recovery to the 7th UNCAC Conference of States Parties that took place in Vienna, Austria, 6-10 November 2017.

Publications by CSOs on Asset Recovery

- Civil Forum for Asset Recovery (CiFAR) – Germany: “Stolen asset recovery between Germany and developing countries”

- Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice (ANEEJ) – Nigeria: “Tackling poverty with recovered assets: the MANTRA Model”

Key resources

- StAR Asset Recovery Watch Database and Settlements Database

- Transparency International: “Calling for Transparent and Accountable Asset Recovery – TI Country Reports” (Statement submitted to the 8th UNCAC CoSP; 2019)

- UNCAC Coalition: “Towards a Comprehensive, Effective, Transparent and Accountable Implementation of UNCAC Chapter V” (Statement submitted to the 7th UNCAC CoSP; 2017)

- Few and Far: The Hard Facts on Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR Series; 2014)

- Left out of the Bargain: Settlements in Foreign Bribery Cases and Implications for Asset Recovery (StAR Series; 2014)

- Guide to the Role of Civil Society Organisations in Asset Recovery (Arab Forum on Asset Recovery; 2013)

- On the Take: Criminalizing Illicit Enrichment to Fight Corruption (StAR Series; 2012)

- Public Office, Private Interests: Accountability through Income and Asset Disclosure (StAR Series; 2012)

- Asset Recovery Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners (StAR Series; 2011)

- Barriers to Asset Recovery: An Analysis of the Key Barriers and Recommendations for Action (StAR Series; 2011)

- Development Assistance, Asset Recovery and Money Laundering: Making the Connection (ICAR Brochure; 2011)

- Recovering stolen assets: a problem of scope and dimension (Transparency International Working Paper; 2011)

- The Puppet Masters: How the Corrupt Use Legal Structures to Hide Stolen Assets and What to Do About It (StAR Series; 2011)

- Politically Exposed Persons: Preventive Measures for the Banking Sector (StAR Series; 2010)

- Towards a Global Architecture for Asset Recovery (StAR Report; 2010)

- Stolen Asset Recovery: A Good Practices Guide for Non-Conviction Based Asset Forfeiture (StAR Series; 2009)

- The Recovery of Stolen Assets: A Fundamental Principle of the UN Convention against Corruption (U4 Brief; 2007)