31 October 2015, by Tilman Hoppe.

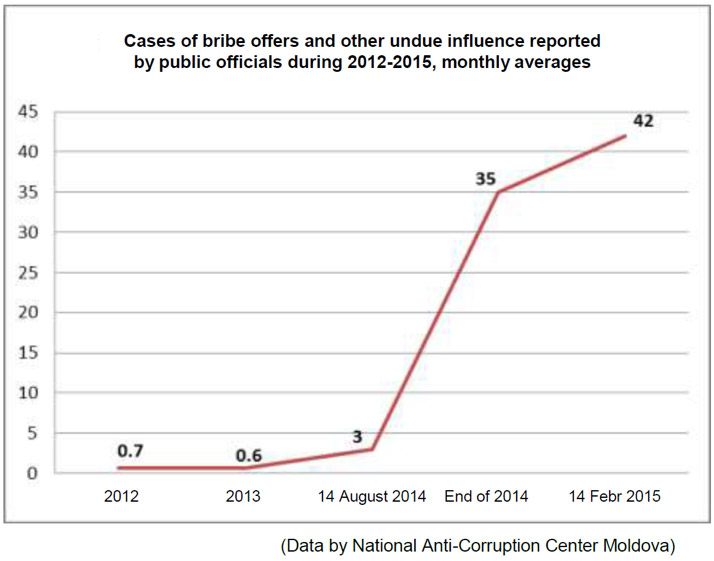

On 14 August 2014, the Republic of Moldova broke the culture of silence around bribery. The number of public officials reporting bribe offers soared strikingly within days.

But what had happened?

Moldova simply installed a tool, which not only Transparency International but also international organisations including the OECD, OSCE, UNODC and the World Bank have recommended for years. It is a tool that has been part of the success story of Georgia, and long-standing rule of law democracies such as Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States apply it in their police forces. The tool is called integrity testing.

It involves undercover testers, pretending to be ordinary citizens, going around the country and applying for public services. Before the testing began all public officials were warned and the National Anti-Corruption Center also conducted 472 training sessions for public officials on how to properly respond to bribe offers.

The tests had the following immediate effects. Public officials were more hesitant in asking for bribes, because any citizen in front of them was a potential integrity tester. Public officials also started reporting bribe offers from citizens: they suspected these offers to be integrity tests and wanted to demonstrate their integrity. This had the knock-on effect of reducing the number of citizens offering bribes, because public officials had started reporting them. It is no wonder that the European Union strongly encouraged Moldova to continue applying this new tool.

So, given the effectiveness of integrity testing, why is it not applied in many more countries? The answer is simple: because it is so effective. Applied properly, integrity testing has the potential to dry up the stream of revenue from bribery. So it steps on many toes.

Of course, this tool raises constitutional law questions. Do the tests violate the privacy of public officials because testers secretly record them? To what extent are testers entrapping public officials if they offer bribes? But, what practical weight do such questions carry in a country where court decisions can depend on who is paying the bribe?

Moldova tried to mitigate the constitutional risks with a simple innovation. The tests had no criminal implications, neither for the tester investigators nor the public officials, and the tests could not be used in criminal trials. But, the tests were used to fire all public officials recorded on video asking for a bribe.

Other countries should watch Moldova – it is building up a rich experience on integrity testing and it is doing so fast.

About Tilman Hoppe

Dr. Tilman Hoppe is an anti-corruption expert based in Berlin.