29 October 2012.

28 September 2012 was the 10th anniversary of International Right to Know Day, proclaimed by the Freedom of Information Advocates Network (FOIAnet) in 2002. Much has happened over those ten years. FOIAnet itself has grown from a meeting of just twenty individuals, mostly from European countries, to a truly international network bringing together over 200 organisations and more than 600 people. The number of countries with right to information laws has more than doubled, from just 42 to 93. Perhaps most importantly, the right to information is now firmly recognised as an internationally guaranteed human right.

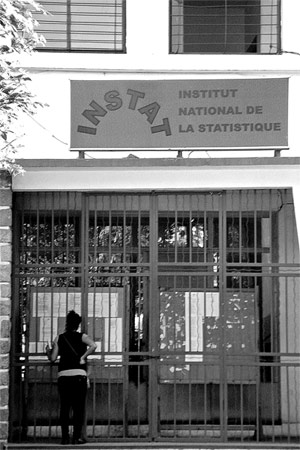

Photo credit: Tolojanahary Ranaivosoa, winner of the photo contest organized by FOIAnet to celebrate Right to Know Day 2012

The office of the national institute for statistics is closed, but the young woman is nevertheless taking notes from the papers published at the door.

In its 10-10-10 Statement (10 achievements, 10 challenges and 10 goals), FOIAnet highlighted a number of important challenges that remain ahead of us. Less than one-half of the world’s States have adopted right to information laws, and implementation remains weak in many of those which have laws. Some countries have witnessed a backlash against the right to information, with attempted legal clawbacks and a disturbing growth in physical attacks on activists. FOIAnet is committed to do what it can to address these and other challenges.

From the very beginning, right to information advocates have always recognised the important role it can play in combating corruption and other forms of wrongdoing. Indeed, this has been a very strong selling point for right to information laws in the face of sometimes sceptical governments. It must therefore be counted as a success that the last ten years have also seen the adoption and coming into force of the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). Of particular note is Article 10 of UNCAC, which many advocates have interpreted as requiring States to adopt right to information laws.

The power of right to information to combat corruption operates at several levels. At its most obvious, this right is a tool that can be used by the media and civil society to expose and control corruption. At another level, a structural shift to greater openness makes it more difficult to engage in corruption in the first place, both because it is more difficult to operate in the secrecy that corruption requires and because the risks of getting found out are greater. At a third level, openness engenders a change of attitude, both within government and among the wider citizenry, with a shift to the idea that government exists to serve the people and that it belongs to the people. While this is unlikely to stop entrenched corruption, it can certainly help limit its growth.

FOIAnet is looking forward to another ten years of successful cooperation in support of transparency, both among its members and with a wider global set of stakeholders. We look forward to enjoying increased benefits from right to information over time, including lower levels of corruption but also greater government accountability and more, and more meaningful, participation in governance.

Toby Mendel

Chair, FOIAnet

Executive Director, Centre for Law and Democracy