20 October 2023 –

As one of the highest-risk areas of corruption for governments, promoting integrity in public procurement is crucial. Article 9.1 of the UNCAC emphasizes taking the necessary steps to establish appropriate systems of procurement, based on transparency, competition and objective criteria in decision-making, that are effective in preventing corruption. Public procurement corruption rarely involves just one single individual responsible for corrupt behavior, but rather a series of actors at the various stages of procurement. This issue was highlighted in the 13th Asia-Pacific Regional Meeting of the UNCAC Coalition. The meeting gathered Asia-Pacific members, affiliated groups and colleagues from the UNCAC Coalition. Regional Coordinator for Asia-Pacific, Fatema Afroz, opened the meeting and set the tone for discussion on the topic.

Fighting corruption in procurement: Indonesia Corruption Watch advocates for monitoring

Wana Alamsyah, head of the Knowledge Management Division, lead of the Digital Security System at Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), and a member of the Coordination Committee of the UNCAC Coalition’s Board presented the context of Indonesia and ICW’s work to identify fraudulent activities and advocate for positive change. ICW has contributed to the oversight of public procurement monitoring platforms.

To encourage public oversight and push for open contracting in the public sector in Indonesia, ICW studied the vulnerability of public contracting to corruption. The evidence showed that between 2016 and 2019, more than 40% of the corruption cases per year were, in some way, related to public contracting. ICW developed tools, such as opentender.net – a digital monitoring platform, to identify potential fraud in the procurement process. With adequate knowledge and technical know-how, ICW presented it to the National Public Procurement Agency (NPPA) as a strategy to get attention from them and garner momentum to collect data from all the institutions in the country. With the assistance of the Open Contracting Partnership, ICW is developing a feature for the public to create a report which will be directly forwarded to NPPA: the agency that will facilitate a complaint-handling mechanism. To encourage public engagement in anti-corruption in public procurement, ICW is working to enhance collaboration among citizens, CSOs, journalists, and internal auditors to monitor public procurement through Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) methods. ICW is also working on capacity-building initiatives and awarding investigative fellowships for journalists interested and working in the public procurement sector.

Wana then presented the challenges of tackling corruption in public procurement in Indonesia. He considered data integration as a major challenge. ICW found that state-owned companies have no obligation to integrate data into national procurement agencies. Indonesia is also in need of a law on public procurement which includes state-owned companies. An additional challenge is the lack of implementation of policies relating to freedom of information. By law, the public body is obliged to publish open public procurement data that is not showing good compliance. Yet, requests for such information have been denied. While a mechanism for judicial action exists if the required information is not shared, a private company can also be sanctioned by a public body if it hasn’t provided the required information in a timely manner.

Empowering citizens through open contracting: WeSolve advocates for building better bike lanes in the Philippines

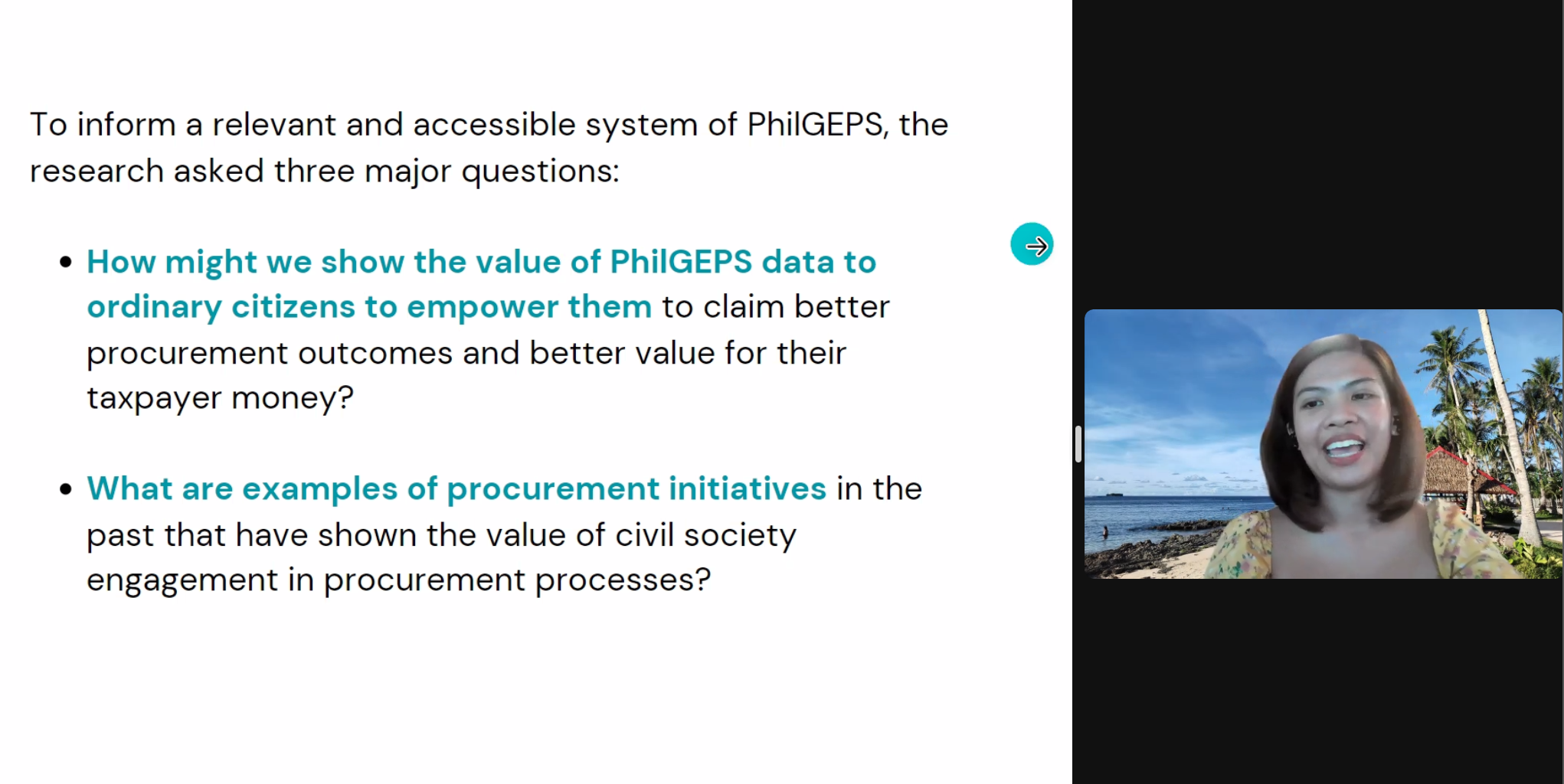

Riz Supreme Balgos Comia, Senior Associate from WeSolve Foundation, a youth powered coalition in the Philippines, presented a case study on bike lanes. Aiming to empower citizens for better procurement outcomes, WeSolve studied the procurement cycle of bike-lane construction in the Philippines. Using a multilateral initiative engaging all relevant government entities, they found a need for improved statistical disclosure for effective participation in the procurement process.

WeSolve’s study found a gap between the data provided online and the real bidder on the ground. The study also assessed the institutional arrangements of the Philippines Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGEPS), discovering that PhilGEPS is under-resourced and understaffed, with no permanent positions. WeSolve found open contracting very crucial and considered effective only when proactive and accessible from the stages of planning to evaluation and quality assessment. The proactive invitation of civil society to participate in the procurement process, which at present is only occasionally done, is instrumental for its successful implementation. Riz also shared that procurement in the Philippines is erratic: civil society is sometimes allowed to join based on the conditions of non-disclosure agreements.

WeSolve recommends enhancing transparency, participation, and accountability mechanisms to improve procurement procedures. A ‘book-end approach’ was proposed so that before bidding, CSOs can comment on design standards for the preparation of the annual procurement plan. They call for a ‘procurement integrity movement’ to co-create stronger and more inclusive open contracting commitments, and foster a safe and empowering environment for the emergence of young public procurement leaders.

The presentations were followed by a vibrant discussion that included stories about projects monitoring procurement shared by participants from Malaysia, Kyrgyzstan and Indonesia. Typically, civil society’s role includes identifying suspicious events, labeling red flags, checking violations, conducting investigations, filing complaints, and so forth.

On a positive note, there have been successful examples of creating appropriate legal regimes, e-tendering and disclosures of information in the procurement sector. On the other hand, bad practices include creating detrimental laws that obstruct open platforms: disclosing tender information only after the award is granted does not help monitoring efforts. Phenomena such as ‘coalition tender”, ‘nepotism’, ‘conflicts of interest’, ‘political corruption’ in the context of procurement also punctuated the discussion. Anti-corruption CSOs in the region are increasingly broadening their work to advocate for establishing transparent, accountable and appropriate systems of procurement.