11 July 2022 –

In times of crises, access to information suffers. On account of the Covid-19 pandemic and of violent political conflict, some governments in Europe have restricted information disclosure and are exercising ever-increasing controls over plural media and social media. But guaranteeing access to information is not a superfluous expenditure. On the contrary, our understanding of the essential role of access to information, for democracy in general and for the fight against corruption in particular, has considerably grown since the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) entered into force in December 2005.

On June 30, the UNCAC Coalition’s Europe network gathered for its 3rd regional meeting to address this topic of high interest to many anti-corruption organizations. Over 20 participants discussed challenges of access to information and how organizations are exercising, demanding and also pushing the boundaries of the right to access information. The meeting’s three main presentations showed different perspectives and current challenges to access to information in Albania, Armenia and at the level of European Union institutions.

The UNCAC Coalition’s Access to Information Campaign and reluctance in Europe to release information

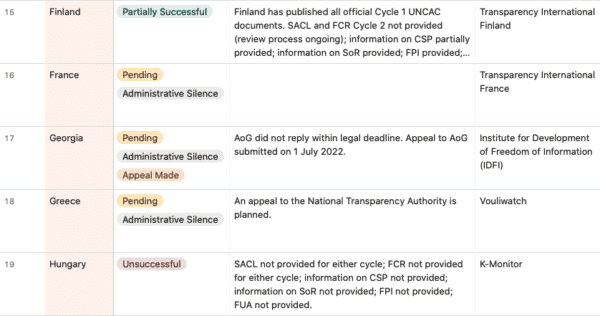

After some Coalition updates by Danella Newman on recent and upcoming events (check out the newsletter and emails on the mailing lists!), Denyse Degiorgio from the Coalition’s Vienna Hub presented the ongoing Access to Information Campaign on UNCAC review documents and how it is progressing in Europe. The campaign appeals to governments to release official UNCAC documents through Freedom to Information (FOI) requests. Using the Coalition’s request templates, national civil society organizations (CSOs) are asking for a variety of documents including the self-assessment checklist, the full country report, information on civil society involvement and on the UNCAC review process in the country, such as the focal point. Releasing these documents is not mandatory and governments are encouraged, but not obliged to involve civil society in the UNCAC review process. Therefore, this campaign is an opportunity for governments to show how committed they are to transparency and to implementing the UNCAC by making information publicly available.

The findings of the campaign to date show that in Europe, FOI requests have already been sent in 14 countries. In Hungary, the government postponed the deadline for response to FOI requests to up to 90 days justifying this by using arguments related to Covid-19. In some countries such as Croatia and Albania, organizations made appeals to national information commissioners and these resulted in orders to release information and disclose documents. Also, at least two states have refused to disclose information based on the Terms of Reference of the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation, which, however, state that “the State party under review is encouraged to exercise its sovereign right to publish its country review report or part thereof”. Any CSO interested in joining the campaign can write to ati@uncaccoalition.org for more information on how to get started.

State of play of access to information in Europe and tips to submit FOI requests

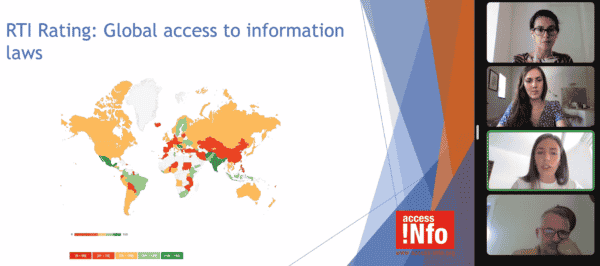

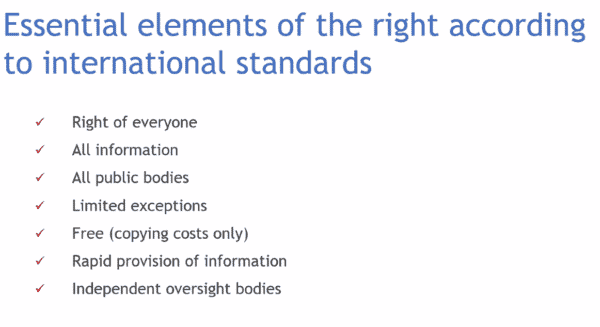

The round of presentations was kicked off by Rachel Hanna, Legal Researcher and Campaigner at Access Info Europe, with an overview of access to information in the region at both the European Union (EU) and in individual countries. As an overarching legal framework, the first binding treaty on access to official documents (known as the “Tromsø Convention”), which was adopted by the Council of Europe and entered into force in December 2020, has been ratified by 12 countries so far. Access to information is a fundamental right, but it is not an absolute right and can be limited. However, exceptions should be justified through both a harm test and a public interest test: information should be published whenever the public interest outweighs the possible harm of disclosure. These international standards are not always applied. For example, Regulation 1049/2001, the EU’s freedom of information law, is based on a narrower definition of information and only grants access to “documents” from EU institutions.

At the national level, the Right to Information or RTI rating shows the diverse quality of access to information laws across the globe. Some of the best laws can be found in South-East Europe (Serbia, Slovenia, Albania, Croatia) while the weakest law, according to this ranking, is that of Austria (and the prospects for a sound freedom of information act are not very promising either). But it is one thing to have good laws on paper and another to enjoy the right of access to information in practice. Besides, another problem is whether current laws are fit for purpose in the digital age. In this sense, the EU Commission has worryingly considered that text messages do not fall under EU transparency rules and is denying public access to text messages between EU Commission President Von der Leyen and the CEO of Pfizer regarding Covid-19 vaccine contracts.

Finally, Rachel gave very useful tips to submit FOI requests. Firstly, it is important to prepare and plan ahead, by analyzing the law, finding whether the body you will submit the request to falls under the law and checking the rules about fees. Secondly, she recommended to start out with a simple request to avoid outright rejection of the request or clarification questions. Thirdly, ask preferably for electronic documents and show that you know your rights – in some circumstances, it might help to mention that the request is submitted under the state law. If information is denied, we should look at what exception has been put forward and if harm and public interest tests have been properly applied, before contacting the Information Commissioner or a judicial body in charge. Find Rachel’s full presentation here.

Finally, Rachel gave very useful tips to submit FOI requests. Firstly, it is important to prepare and plan ahead, by analyzing the law, finding whether the body you will submit the request to falls under the law and checking the rules about fees. Secondly, she recommended to start out with a simple request to avoid outright rejection of the request or clarification questions. Thirdly, ask preferably for electronic documents and show that you know your rights – in some circumstances, it might help to mention that the request is submitted under the state law. If information is denied, we should look at what exception has been put forward and if harm and public interest tests have been properly applied, before contacting the Information Commissioner or a judicial body in charge. Find Rachel’s full presentation here.

Using access to information to access other rights in Albania and Armenia

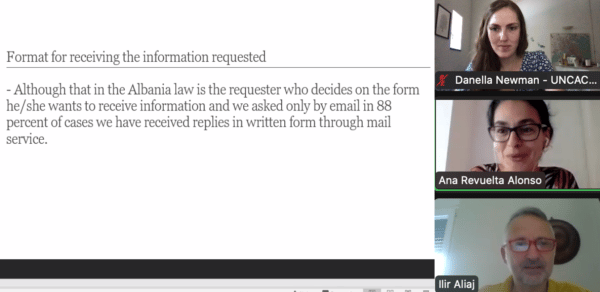

Ilir Aliaj, Executive Director of the Centre for Development and Democratization of Institutions (CDDI), shared insights into their recently concluded project “Transparency of local administration in Albania”. Through information requests, CDDI monitored implementation of the Albanian law on freedom of information in the 10 biggest municipalities of the country. Requests asked for information on revenues and budget, projects financed or decisions taken by the Municipality Council, public consultations conducted, but also sensitive information like CVs of the municipality’s directors, number of employees and their salaries.

The results of the project have not been very encouraging. Only two municipalities gave access to all information requested and respected the 10-day legal deadline. Most municipalities provided partial information and, in some cases, like in the capital Tirana, a response was received after 24 days from the submission date. Requests for directors’ CVs were denied on the grounds of article 7 of the Albanian Access to Information law which, however, states that data on education, qualifications and salaries of all directors are public. No information was received concerning public consultations, the number of employees and their salaries.

This project exemplifies how a good access to information law does not ensure that the right to access information is respected. Moreover, if basic questions are not responded to, information on more complex areas like public procurement will be even more difficult to obtain. Therefore, Ilir insisted on continuing to advocate for the implementation of the law. Find Ilir’s full presentation here.

In the last presentation, Shushan Doydoyan, President of the Freedom of Information Center of Armenia (FOICA), highlighted that access to information is the key to “open” all other human rights and that little space remains for corruption when strong access to information laws and mechanisms are in place.

As she explained, FOICA is focusing on using access to information as a tool against corruption, as a tool against disinformation, and for getting access to beneficial ownership data. A good example of how access to information may lead to political reforms started several years ago, with an information request to the President’s Office of Armenia on state funding to civil society organizations. FOICA received a complete and timely answer but, after checking the accuracy of the information, found that some organizations mentioned did not exist or were not functional. Eventually, these findings resulted in a comprehensive reform of the allocation of state grants to civil society organizations, to make the process more transparent and competitive.

The second issue was disinformation, which FOICA began to tackle recently as it has become a huge concern in Armenia with media and social platforms flooded with false news and manipulations. While the government is spending considerable resources to manage disinformation risks, it fails to recognize that the first tool against it is reactive and proactive access to public information. When this right is not guaranteed, an information vacuum is created and either filled with fake and manipulative information or remains void, compromising trust in public institutions. To counter this situation, FOICA is monitoring all websites of governmental institutions and issuing concrete recommendations to demand that public information is fully disclosed, in a timely manner and in open data formats. The organization has also been mandated with developing a three-fold strategy for the government, to be adopted soon, which seeks to strengthen capacities of state institutions against disinformation, mobilize the private sector and train civil society.

Lastly, Shushan touched upon the issue of access to beneficial ownership data of private companies, which has become a high priority for the Armenian government in the past years. Upon recommendation from several civil society organizations, the government committed to open up beneficial ownership data of all businesses in the country and adopted related legislation. However, challenges remain: media companies fear that the reform might pose a threat to press freedom and ordinary citizens have to pay a fee to get access to beneficial ownership data. To push for transparency, civil society should continue to find innovative uses for ownership information, for example, by researching any ties business owners may have to local or international political actors and to the financing of electoral campaigns. Proving its usefulness will increase the public demand for access to beneficial ownership data.

Civil society priorities to advance access to information

In a rich debate following the presentations, participants raised concerns and made proposals on what anti-corruption organizations should concentrate on to advance the right to access information. In particular, we discussed the following:

- Innovative ways to overcome newly-emerging grounds for refusing information: Increasingly, information requests are being denied with arguments of privacy of public officials or commercial interests. Besides advocating for the public interest test to be applied, we can also advocate for the digitization of public information and processes. As all countries move towards digitalizing databases and records, information will become more easily accessible and trackable, and costs will be saved.

- Evidence on the costs and the benefits of transparency: The implementation of the EU Open Data Directive is experiencing pushbacks on the grounds of its cost. However, recent reports (here and here) conclude that the economic and social benefits of opening up company registers outweigh the costs. In the case of the Austrian draft law on access to information, its adoption is being delayed partly using the argument of high costs and the belief that local governments will be overwhelmed by FOI requests. Statistics on information requests, which are available in some countries, together with international examples such as those from Albania and Armenia, might prove that lack of access to information regulation represents a cost in terms of rising corruption and that investments in transparency pay off in the long-run.

- Changing the status quo and inspiring a spirit of transparency: As a conclusion, there was consensus that we need to work on building a culture of transparency, and review the concept and the legal definition of information in an ever-changing and increasingly digital world. We have to keep raising awareness of the fact that information held by the government belongs to the public. Many citizens across Europe still do not know or understand how simple it may be to request information from public bodies and to get it. As civil society organizations, we have valuable insights and experience to share and contribute to change the status quo.