13 May 2025 –

Guest blog by Maria Gabriela Sarmiento, summarizing research she undertook between 2018 to 2021 as part of her PhD degree in Law, at the University of Zaragoza. Her findings and positions don’t necessarily reflect those of the UNCAC Coalition.

Every year, developing countries lose between $20 and $40 billion to corruption practices such as bribery, embezzlement and money laundering. These illicit funds often find refuge in offshore financial hubs, with Switzerland being one of the most prominent. But how much of this money is ever returned to its rightful owners? And how transparent are these processes?

This article distills five years of meticulous PhD research into transparency in grand corruption and asset recovery cases in Switzerland between 1985 and 2025, offering a rare glimpse into an otherwise opaque system. This research was originally published in Spain in 2023, and updated in 2025 to showcase some unprecedented and unreleased findings during the 18th Session of the Asset Recovery Working Group at the UNCAC Coalition.

The billion-dollar question: Where does the money go?

Switzerland has long been a preferred destination for assets looted through grand corruption. Between the identified time period, assets from at least 33 jurisdictions have been traced to Swiss banks. These are primarily proceeds of grand corruption, money laundering and other crimes, with estimated values fluctuating between $112 billion and $514 billion.

Yet, there is no single official register in Switzerland tracking these illicit assets—no consolidated data on amounts frozen, forfeited, or returned. Judicial decisions are often anonymized, and agreements terminating investigations are kept confidential. This lack of transparency has made systematic asset recovery extremely challenging.

Landmark cases and major recoveries

Despite these challenges, Switzerland has returned significant sums over the years. According to official figures, from the early freezing of Ferdinand Marcos’ assets in 1986 to recent recoveries, the country has restituted more $2.1 billion to nations affected by grand corruption. However, this research concludes that more than $3.1 billion have been restituted, as shown in the table below.

Among the largest beneficiaries:

- Nigeria: Over $1 billion returned across multiple cases (Abacha I, in 2005 & Abacha II, in 2017).

- The Philippines: $684 million from the Marcos case.

- Brazil: $567 million recovered from corruption scandals.

Other notable recoveries include:

- Peru (Fujimori-Montesinos cases): $116 million.

- Kazakhstan (Nazarbaev cases): $163 million.

- Uzbekistan (Karimova case): $313 million.

In total, fourteen jurisdictions have received recovered assets from Switzerland.

In 2022, there were twenty-three countries subject to Swiss economic sanctions. The most impacted regions are sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East according to Table n° 2 (below). These cases can be found at the Secretary of the State (SECO) website. Economic sanctions foresee the freezing of assets and economic resources derived from crime. The sanctions also state the prohibition of making these assets available to their owner.

The cases we don’t hear about

While these figures are impressive, they represent just a fraction of the total illicit wealth that likely passed through Swiss financial institutions. Our research estimates that globally, between $680 billion and $1.36 trillion have been lost to corruption between 1986 and 2025. Yet, by 2025, only $10 billion had been recovered worldwide—of which Switzerland accounts for roughly one-third.

The disparity is staggering: the $10 billion recovered globally might represent just 0.85% of the total illicit funds siphoned from developing countries.

Barriers to recovery: Political will and legal obstacles

One of the main hurdles in asset recovery is the lack of political will—both in Switzerland and in the countries of origin. Kleptocratic regimes rarely cooperate in providing evidence of illicit asset origins. Offshore financial centers, on their part, often show limited interest in initiating complex investigations without external pressure.

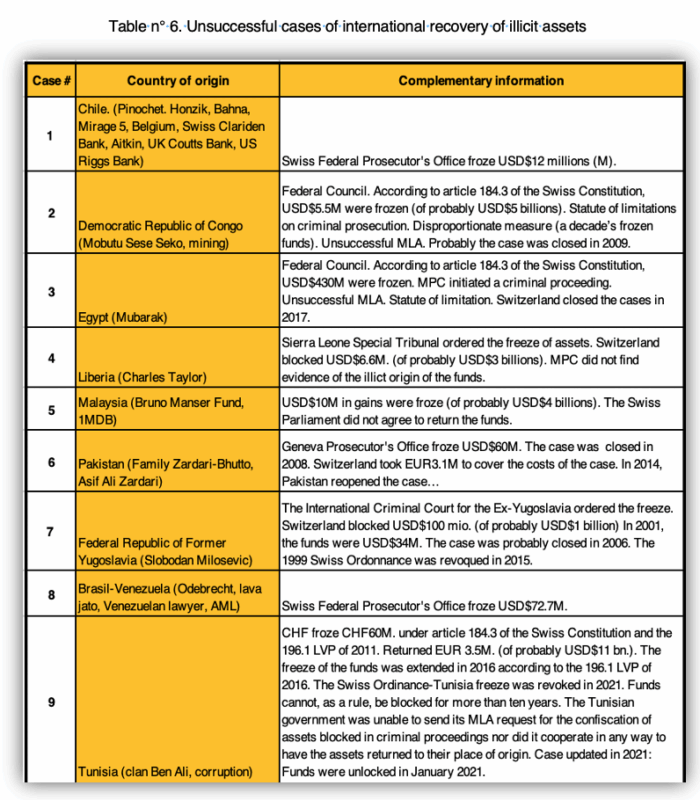

Some unsuccessful cases of international recovery of illicit assets are captured in the table below.

Even when assets are traced and frozen, insufficient evidence or political inertia can stall their return for decades. Some assets have remained frozen in Switzerland for over 20 years, only to eventually be returned to the families of the corrupt officials who embezzled them in the first place.

The critical need for more transparency

Switzerland’s asset recovery processes remain notoriously opaque. Unlike the World Bank-UNODC Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR), which attempts to track global recovery efforts, Swiss authorities do not maintain a comprehensive, publicly accessible database. That said, the StAR database is unable to provide an up-to-date, comprehensive, and accurate picture.

Improving transparency is critical. For an accurate decentralized registry of Asset Recovery Cases, we recommend encrypted and immutable blockchain-based registries which, once recorded, data cannot be altered without changing subsequent blocks, each containing data, timestamps, and cryptographic hashes linking to the previous block.

Switzerland has played a significant role in global asset recovery, returning more illicit assets than any other country. However, this should not overshadow the pressing need for greater transparency and systemic reforms.

For as long as secrecy and fragmented data persist, the world’s kleptocrats will continue to exploit financial loopholes, and developing nations will struggle to reclaim their stolen wealth.

Thesis extracts (in Spanish):

- Figure n° 2 Ex officio freezing orders by the Federal Council

- Table n° 2 Countries subject to Swiss Economic Sanctions

- Table n° 5 Asset recovery cases in Switzerland Frozen assets pending for forfeiture and return (Estimates)

- Table n° 6. Unsuccessful cases of international recovery of illicit assets

- Table n°3. Successful cases in Switzerland of restitution of assets derived from crime

- References