9 August 2016, by Jackson Oldfield.

This post was originally published on the Civil Forum for Asset Recovery website.

When we talk about the theft of public assets and their return, we often get into a discussion of ‘destination countries’, ‘tax havens’ and ‘victim countries.’ These terms roughly correspond in most of our minds to:

- Destination countries: Rich, developed countries with steadily increasing property markets and stable banks

- Tax Havens: Island nations with large banking sectors and high levels of secrecy

- Victim countries: Developing countries with either poor oversight of public sector finances or some form of dictatorship where criticism of the theft of public money is restricted

These characterisations are, of course, at best only partially true and at worst false. In either case they skew our thinking about what is at heart an interlinked, international web of corruption.

Let’s start with destination countries. The term alone makes the role of countries where public assets are being hidden by corrupt officials seem passive. In fact, many of these destination countries do not put in place all the measures they could to restrict the flows of corrupt money, in other words they too act as tax havens – or as they are increasingly called, secrecy jurisdictions.

Switzerland, the UK, France and the US are not only the favoured destinations of hidden wealth by corrupt officials, they also all rank highly in the Financial Secrecy Index, meaning that they are countries that have measures in place that facilitate the hiding of corrupt wealth in their country, such as allowing secret bank accounts or anonymous trust and company ownership. The US state of Delaware for example is one of the easiest places in the world to open an anonymous company – used by the corrupt to hide the traces of their wealth.

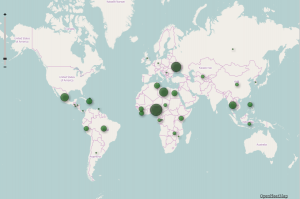

Similarly, victim countries are not always purely victims, for example Panama, as well as now being a famous secrecy jurisdiction, is also currently attempting to recover some of its stolen public money hidden in France. Nor do victim countries conform to a pattern, as can be seen in the map below of countries initiating proceedings to recover stolen assets, they span the globe.

Countries of origin with ongoing cases listed in StAR’s Asset Recovery Watch database as of November 2015

When we speak about asset recovery then, perhaps we should rather speak of victims, enablers and perpetrators, all of whom exist regardless of geographical location.

The victims are always the people, their public money – money for schools, hospitals and welfare – has been stolen.

The enablers and the perpetrators? They are the banks who don’t do proper customer checks, the law firms that set up shell companies, the politicians who don’t pass the laws to stop corrupt money flowing into or through their countries, and the officials who enrich themselves at the expense of others.

Perhaps changing how we define the actors involved in public asset theft will help us to move beyond seeing some countries as passive recipients and some as tragic cases and instead recognise that this is a global industry, with global players and one that needs to be fought on a global scale.