23 October 2025 – written by Pablo Herrera, Regional Coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean

In many Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries, where impunity persists and results in combating corruption remain limited, asset recovery often becomes one of the few remaining avenues to achieve justice. Beyond recovering stolen or corruption-originated resources, it represents a chance to restore public trust, repair social harm, and strengthen accountability. The 21st Regional Meeting for Latin America and the Caribbean of the UNCAC Coalition explored this potential, highlighting how civil society organizations (CSOs) can play a decisive role — from identifying cases and building investigative databases, to promoting legal reforms, advocating for transparent return mechanisms, and designing models for the social reuse of recovered assets. The session also fed into our region’s collective input to CoSP11.

Why asset recovery, and why now?

Transnational and large-scale corruption erodes trust, drains public coffers, and crosses borders faster than accountability can follow. Despite having UNCAC Chapter V in place, implementation gaps remain significant. LAC members emphasized that recovery must go beyond freezing and confiscation to transparent management and use of assets for reparation, justice, and prevention, especially for affected communities.

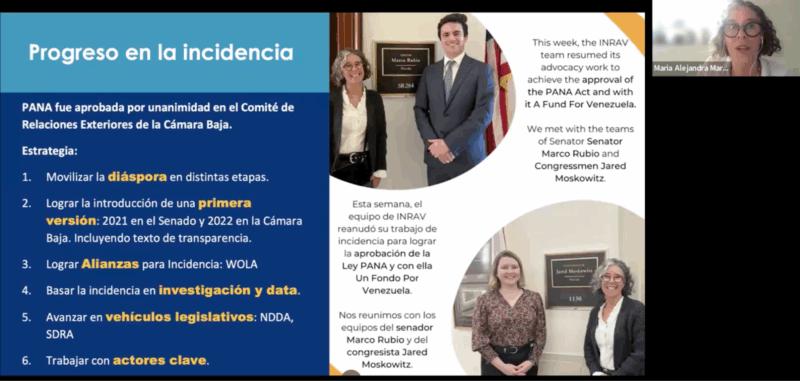

Mapping corruption and advancing advocacy from Venezuela

María Márquez, Executive Director of INRAV, the Venezuelan Asset Recovery Initiative, walked us through a civil-society strategy that treats asset recovery as a human-rights imperative. The jurisdictional reality shows that traditional state-to-state returns are blocked in the U.S. context, or tend to present several obstacles in different jurisdictions; Venezuelan institutions lack the capacity and legitimacy to claim case-by-case returns. Taking a legislative approach, INRAV advocated for the passing of the PANA Act (Preserving Accountability for National Assets Act of 2023), proposing a U.S.administered Venezuela Restoration Fund to channel confiscated proceeds into strengthening governance, human rights, independent media, and anti-corruption, with transparency and oversight safeguards. The campaign draws on the power of the diaspora, bipartisan engagement, and evidence tools, including INRAV’s Venezuela Loot Tracker. Finally, aiming to place victims at the center, she highlighted INRAV’s engagement in developing a fund model for the transparent social reuse of confiscated and recovered assets, in collaboration with the World Bank, the Civil Forum for Asset Recovery (CiFAR), and the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). These models propose a mechanism to ensure that assets repatriated from Venezuelan actors in the United States are used for reparation, development, and the benefit of affected communities.

INRAV presented the organization’s Loot Tracker— a pioneering Venezuelan database developed with the use of artificial intelligence that documents 72 cases of corruption and asset diversion involving public officials and private actors. This innovative tool aims to centralize and analyze case data to support investigations, journalistic work, and advocacy efforts.

Beyond the mechanics, the strategy underlined a broader lesson for CSOs: the need to pair rigorous data with legislative advocacy and coalition-building to unlock creative, rule-bound return models when executive-branch discretion alone tends to sideline victims.

Transparency and accountability in non-trial resolutions: promise and pitfalls from the Odebrecht saga

Guilherme France, manager of the Anticorruption Knowledge Center from Transparency International Brazil, shared insights on non-trial resolutions in foreign bribery cases, reflecting on lessons learned from the Odebrecht case, one of the largest corruption schemes in modern history, spanning 12 countries and involving over 100 projects.

He explained that non-trial resolutions can be powerful tools to promote asset recovery and accountability when implemented transparently and with judicial oversight. However, he warned that in many jurisdictions, these agreements suffer from insufficient sanctions, lack of transparency regarding the details of bribery, and absence of alternative penalties if agreements fail.

France also emphasized that countries lacking judicial independence face particular challenges in enforcing such resolutions and recovering assets. He pointed to the need for stronger international cooperation and monitoring, as well as civil society’s role in ensuring that leniency agreements, settlements, and plea deals truly serve justice and deter future corruption.

Globally, most resolved cases rely on non-trial resolutions (NTRs); they can speed up outcomes and generate significant penalties. But design matters:

- From unilateral to “global” settlements: The shift from keeping penalties in the enforcing country toward crediting payments in affected jurisdictions is progress – but distribution still skews when multi-country schemes are involved.

- Brazil’s push: Requiring the company to settle with each affected country attempts to localize reparation.

- Reality check: Transparency is weak, deadlines slip, and settlements are absent in jurisdictions with captured justice systems (e.g., Angola, Venezuela). Without public terms, civil society cannot assess proportionality or press for better outcomes.

- Risk ahead: Ongoing renegotiations of leniency deals may lower penalties without addressing foreign-bribery elements, undercutting deterrence and returns.

The takeaway: NTRs are here to stay; our task is to shape them, mandating disclosure, victim-sensitive uses of funds, and default provisions when local settlements are impossible.

The victims’ lens (and where the money actually goes)

Members stressed a persistent blind spot: Who benefits after confiscation? Examples from the region show fines and “social harm” payments – like a legal figure recently created in Costa Rica – often default to treasuries with no earmarking for victims, transparency, or community redress. In the U.S., officials note that victims have legal priority on paper, yet closed-door allocation meetings can route resources to institutional budgets instead. Our shared priority: codify victims’ participation and safeguards in any fund or settlement, and insist on public reporting of inflows, outflows, and impact.

What civil society can do (starting tomorrow)

- Map and monitor: Build or contribute to open case trackers that document orders, amounts, and disposition (e.g., INRAV’s Loot Tracker).

- Legislate for integrity: Advocate return mechanisms with statutory transparency, independent oversight, and victim-first mandates, including when state-to-state returns are blocked.

- Raise the floor for NTRs: Demand publishing of settlement terms, cross-border cooperation commitments, and contingency clauses for non-cooperating or captured jurisdictions.

- Replicate what works: Several members called for porting successful designs (fund governance models, disclosure templates, diaspora engagement) across countries rather than reinventing the wheel.

Our regional agenda towards collective action and CoSP11

The meeting also served as a space for members to provide final feedback on the regional submission for CoSP11, the upcoming Conference of the States Parties to the UNCAC, in Doha. As regional members continue to collaborate on these fronts, one takeaway was clear: civil society’s engagement is crucial to ensure the effective implementation of the Convention that asset recovery efforts translate into tangible justice.

For deeper context, see our Working Group’s fresh report on country-level information and data availability in asset recovery—available here.

If you are a civil society activist from Latin America and the Caribbean and would like to become involved, please contact our Regional Coordinator Pablo Herrera at pablo.herrera@uncaccoalition.org.