6 December 2024 –

While the biggest election year ever is coming to an end, the financing of political parties and campaigns continues to grapple with significant challenges. These include opaque funding sources, undue influence from powerful donors, sometimes involving foreign actors abusing the system, and weak regulation enforcement, in Europe and globally. Against this background, a group of civil society organizations from across Europe dedicated the 15th Regional Meeting of the Europe network on November 28, to examining the weaknesses in political finance regulation within the region and proposing initiatives to enhance transparency and integrity in political funding practices.

Despite being a critical element for healthy democracies, with high corruption risks, the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) dedicates only Article 7.3 to acknowledge the importance of ensuring transparency in political finance, as a means to prevent corruption. Article 7.3 encourages States to take “appropriate legislative and administrative measures (…) to enhance transparency in the funding of candidatures for elected public office and, where applicable, the funding of political parties.” Furthermore, to date, the UNCAC Conference of the States Parties (CoSP) has not issued any resolutions to provide further guidance on implementing this vital provision. In Europe, neither the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) of the Council of Europe nor the European Union (EU) have established unified rules to regulate political party and campaign financing.

Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency in money in politics across Europe

Providing a regional overview, Magnus Ohman, Director of the Regional Europe Office and Senior Political Finance Adviser for the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) kicked off the discussion by emphasizing the vital role of civil society in political finance oversight. Drawing from his experience, he noted that, in most countries, political finance violations are typically exposed by civil society organizations and the media. In turn, political actors tend to fear the potential backlash at the ballot box -the “political sanctions”- more than the administrative or legal sanctions for breaking the rules. This underscores the significant responsibility of civil society to ensure that any violation claims are based on rigorous research and verified facts, to avoid allegations of bias that could undermine their credibility.

Another critical issue in political finance oversight and the role of civil society lies in its relationship with public oversight institutions. Every European country has one or more bodies tasked with supervising compliance with party finance regulations, – such as Election Commissions, Anti-corruption Agencies, or Audit Offices-. Civil society has long criticized these institutions for conducting “superficial oversight” and failing to verify the true source of donations, detect money laundering, or identify foreign influence in election campaigns. However, oversight institutions have narrowly defined mandates, usually limited to ensuring transparency by collecting and publishing information. Unlike investigative journalists, auditors and public officials are constrained by domestic laws, and attempting to verify the origin of donations outside these legal frameworks could result in severe consequences for them, including imprisonment. Their roles are defined by strict legal boundaries, which limits their ability to act on suspicions in the way civil society can.

Another critical issue in political finance oversight and the role of civil society lies in its relationship with public oversight institutions. Every European country has one or more bodies tasked with supervising compliance with party finance regulations, – such as Election Commissions, Anti-corruption Agencies, or Audit Offices-. Civil society has long criticized these institutions for conducting “superficial oversight” and failing to verify the true source of donations, detect money laundering, or identify foreign influence in election campaigns. However, oversight institutions have narrowly defined mandates, usually limited to ensuring transparency by collecting and publishing information. Unlike investigative journalists, auditors and public officials are constrained by domestic laws, and attempting to verify the origin of donations outside these legal frameworks could result in severe consequences for them, including imprisonment. Their roles are defined by strict legal boundaries, which limits their ability to act on suspicions in the way civil society can.

Furthermore, Magnus argued that no single institution can meet the growing complexity of political finance oversight. Instead, effective control requires the coordinated efforts of multiple entities, including national intelligence units, specialized police forces, tax authorities, auditors, and prosecutors. If civil society seeks to effectively contribute to enhancing integrity in political finance, it should act on two fronts:

- monitor, investigate, and report suspected violations, by -submitting findings to prosecutors when necessary, rather than solely relying on electoral commissions; and

- advocate for inter-institutional cooperation: beyond demanding greater resources for oversight bodies and legal reforms, civil society can push for improved coordination and collaboration among existing institutions.

Pushing for transparency in political advertising in Hungary

In Hungary, Sandor Lederer, Co-Founder and Director of K-Monitor, argued that opaque political finance has long been a cornerstone of corruption, especially since the country transitioned to democracy. Despite sweeping legislative changes by the Orban government, in power since 2010, the framework governing political finance has remained largely untouched. This inertia reflects the political class’ unwillingness to disrupt a system that enables opaque funding practices and fosters corruption. Key issues that remain untackled include the lack of transparency in party incomes and expenditures, the unregulated involvement of third parties, and the State Audit Office’s limited and politically biased oversight. Despite legal caps on campaign spending, political parties frequently exceed these limits with little consequence. When imposed, sanctions are weak and often selectively enforced, disproportionately targeting opposition parties.

Recognizing the obstacles in pushing for legal reforms in political financing, K-Monitor has shifted the focus to fostering ethical campaigning, particularly at the local level. In the context of the 2024 elections in Hungary, they published a discussion paper on ethical campaigning for local elections to encourage dialogue among stakeholders and establish feasible ethical standards. The local level, being more pluralistic, offers a fertile ground for such efforts from civil society, with broader representation of the opposition and actors more willing to collaborate on setting higher benchmarks for campaign integrity.

Recognizing the obstacles in pushing for legal reforms in political financing, K-Monitor has shifted the focus to fostering ethical campaigning, particularly at the local level. In the context of the 2024 elections in Hungary, they published a discussion paper on ethical campaigning for local elections to encourage dialogue among stakeholders and establish feasible ethical standards. The local level, being more pluralistic, offers a fertile ground for such efforts from civil society, with broader representation of the opposition and actors more willing to collaborate on setting higher benchmarks for campaign integrity.

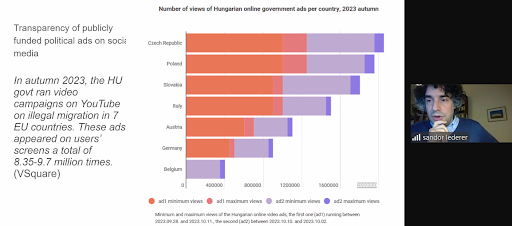

One concrete aspect of political finance that K-Monitor is currently working on concerns the publicly-funded political advertisements on social media, and their lack of transparency. The Hungarian government and ruling party have become one of the biggest spenders of political ads on social media in Europe. They spend significant amounts on platforms like Facebook/Meta and Google, even targeting voters in other European countries with far-right messaging on controversial topics such as migration. Combining their work on political finance and on access to information, K-Monitor is exploring legal avenues to compel greater transparency in these transactions, leveraging Hungary’s Freedom of Information law. The goal is to ensure these private entities, bound by the law to the extent they receive funds from the State, disclose detailed financial information about the source and amounts received. Sandor suggested this effort could be pursued in other European countries as well, to push the boundaries of access to information legislation while also contributing to the transparency of political finance.

A political financing system losing independence in Georgia

Founding member and Executive Director of the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), Giorgi Kldiashvili, presented the evolution of the system of political financing in Georgia until its current status, about which there is widespread concern over transparency and fairness. The Organic Law on Political Associations of Citizens establishes authorized funding sources for parties, such as membership fees, donations, and state-allocated funds (contingent on parties securing at least 1% of the vote in parliamentary elections and based on the number of votes received). Individual donations from Georgian citizens are capped. Contributions from foreign entities, anonymous sources, or public institutions are prohibited, with any such funds redirected to the state budget.

Oversight of political financing in Georgia has undergone significant changes in the last two years. Before September 2023, the State Audit Office was responsible for monitoring party finances, but its independence was often questioned. Following recommendations from the European Commission tied to Georgia’s EU candidate status, the Anti-Corruption Bureau was established as an independent body with expanded powers. This institution now oversees financial disclosures, investigates irregularities, and enforces compliance of political parties with strict transparency standards. Notably, the Bureau has the authority to revoke a party’s registration for financial misconduct and scrutinize campaign finance reports submitted by electoral subjects.

Oversight of political financing in Georgia has undergone significant changes in the last two years. Before September 2023, the State Audit Office was responsible for monitoring party finances, but its independence was often questioned. Following recommendations from the European Commission tied to Georgia’s EU candidate status, the Anti-Corruption Bureau was established as an independent body with expanded powers. This institution now oversees financial disclosures, investigates irregularities, and enforces compliance of political parties with strict transparency standards. Notably, the Bureau has the authority to revoke a party’s registration for financial misconduct and scrutinize campaign finance reports submitted by electoral subjects.

Despite these recent reforms, significant challenges persist. The ruling Georgian Dream party has consistently outpaced its competitors in both official funding and allegations of leveraging undisclosed resources. From January to October 2024, the Anti-Corruption Bureau examined the finances of 16 political parties, with Georgian Dream accounting for the largest share. The Bureau flagged discrepancies in seven parties’ financial disclosures and initiated investigations, while five parliamentary candidates were fined for failing to submit asset declarations. Georgian Dream’s official funding in 2023 significantly overshadowed other parties, with further allegations of a substantial underground budget and misuse of administrative resources.

Civil society plays a critical role in monitoring financial flows to the extent possible, and advocating for greater transparency and integrity in Georgia’s political financing landscape. Tools such as Transparency International Georgia’s reports and databases highlight discrepancies and expose the intertwining of political and economic interests. For instance, the organization documented links between state procurement contracts and party donors, with Georgian Dream donors securing lucrative tenders while contributing millions to the party, thus suggesting systemic abuse of administrative resources. Moreover, the so-called “black budgets” and underground financing remain outside official oversight, amplifying concerns about accountability.

Civil society’s resilience and perseverance amid an increasingly adverse environment

The cases from Hungary and Georgia highlight the impact of opaque and poorly regulated party and campaign financing on democratic institutions. Participants discussed how key institutions like State Audit Offices become politically captured, with counted exceptions, and tend to align with government interests on politically sensitive issues. In Hungary, newer entities like the Integrity Authority hold the promise of overseeing asset declarations, but lack the necessary powers to fulfill their mandate effectively. Meanwhile, Hungary’s judiciary has seen significant erosion, with the Supreme Court now dominated by political appointees, further weakening the rule of law.

Likewise, in Georgia, the Anti-Corruption Bureau has faced criticism for its lack of independence and its apparent alignment with ruling party interests. From its inception, the Bureau has targeted opposition parties disproportionately, restricted access to previously public information about political finance, and taken actions such as attempting to label Transparency International (TI) Georgia as a political party. This decision was reversed only after significant public and international pressure argued the need to maintain observers on the ground as TI Georgia was leading a large civic monitoring effort of the Parliamentary elections in October 2024. The reversal of the decision was announced not by the Bureau but by the Prime Minister on social media.

In a trend that we can see beyond the examples of Hungary and Georgia, institutions that should safeguard public transparency and accountability are instead weaponized against opposition parties and civil society organizations. For the latter, navigating these challenges requires persistence and international support to counter repression. The discussion expanded to the complex political situation in Georgia stemming from the recent elections, which have placed civil society organizations under immense pressure. TI Georgia, IDFI and other civil society organizations and other stakeholders including the European Parliament, have denounced widespread irregularities, including voter intimidation, vote manipulation, and interference with election observers and media. The political climate has significantly restricted civic space, with the ruling party showing growing hostility against civil society organizations that advocate for the rule of law and exacerbating an already difficult situation following the approval of the so-called “foreign agents” legislation earlier this year. Organizations like IDFI are feeling the effects of these measures, with staff reductions and the fear of impending sanctions, and both Transparency International Georgia and IDFI fear being among the first targets of punitive actions. Despite their critical situation, civil society groups remain committed to their mission and determined to continue monitoring and advocating for democratic values.

Resources on political party and campaign finance

- IFES has published Vote for Free: A Global Guide for Citizen Monitoring of Campaign Finance. This guide draws on insights from civil society groups across the world, sharing their experiences in tracking how campaign funds are raised and spent. It serves as a practical resource for organizations seeking to uphold transparency and accountability in political finance.

- The Council of Europe provides guidelines and recommendations aimed at enhancing oversight and integrity, in particular through Recommendation Rec (2003) 4 on rules against corruption in the funding of political parties and electoral campaigns. Political finance was specifically covered in GRECO’s Third Evaluation Round, which began in 2007 and focused on the transparency of party funding within Europe, identifying both achievements and gaps in implementation.

- A study commissioned by the European Parliament in 2021 provided a regional state-of-play of financing of political structures in EU Member States.

- Transparency International held a session on the implementation of article 7 (3) on political finance (in September 2024, during the meetings of the UNCAC Implementation Review Group) and submitted the statement: “Call for UNCAC States Parties to take measures to enhance transparency of the funding of candidates and political parties (UNCAC Article 7.3)”.

- The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) provides assessments on political finance regulations and advocates for better policies to curb undue influence.