4 August 2023 –

Participation of civil society is an essential element in the fight against corruption. Article 13 of the UNCAC requires governments to take “appropriate measures” to involve civil society in fighting against corruption, ensuring citizens have access to information and people have the freedom to share information concerning corruption. However, governments are often seen as not cooperating. Rather many states are seen to restrict civil society organizations working against corruption. Shrinking civic space has become a global concern. The issue gained momentum at the 9th Conference of the States Parties (CoSP) to the UNCAC, where eight leading CSOs were banned from attending due to objections by a state party.

Civic space is also a major concern throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Restrictive laws limit space for civil society to play its role as obliged by the global Convention. The 12th UNCAC Coalition regional meeting of the Asia-Pacific region held on 18 July 2023, highlighted the nature and extent of the shrinking civic space to work against corruption, the challenges, and the ways forward. The meeting gathered Asia-Pacific members, affiliated groups, and colleagues. Regional Coordinator for Asia-Pacific, Fatema Afroz, opened the meeting, set the tone and introduced the presenters and other participants from across the region. The meeting started with a few updates from Vienna including those on the Global Coalition Conference held in June 2023, and the upcoming CoSP10 to be held in December in Atlanta, before the speakers took the floor.

Is Civic Space a challenge throughout the region?

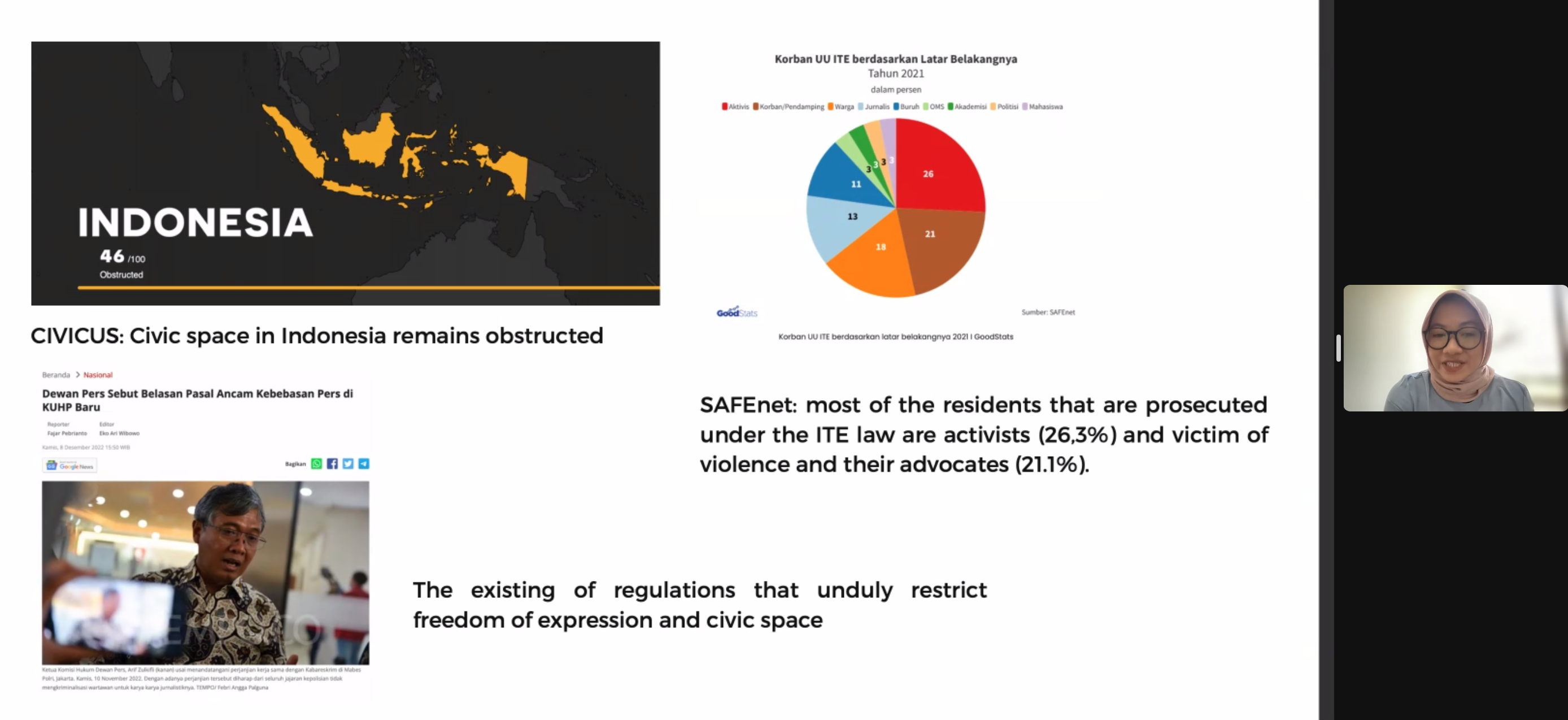

Civic space is a major issue in many countries across the region. Almas Sjafrina, a researcher at Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), reflected on the challenges related to civic space. She emphasized that civic space in Indonesia, with a score of 46/100, is currently classified as ‘obstructed’ by CIVICUS, a global civil society alliance. A number of cases that show a threat to civic space in the country were referred to, including the harassment of two human rights defenders for their comments on a podcast. The case is still ongoing and involved ‘high-level’ Indonesian politicians and public officials.

Has space for freedom of expression improved?

In 2021, a report published by SafeNet claimed that the trend of victims has decreased in Indonesia since 2020. Almas confirmed that this data doesn’t directly indicate the improvement of freedom of expression. Rather, existing regulations unduly restrict freedom of expression and civic space in general. Over the past decade, the government developed a set of policies that shrunk democratic space to an undemocratic policy-making process. One such policy is the Penal Code Law that was passed last year. These are just a few examples of how anti-corruption CSOs in Indonesia experience threats when the cases they are advocating for are related to the police or the members of Parliament.

From physical attack to digital attacks

Observations point to a changing trend in the nature of attacks on civil society. More than a decade ago, physical attacks were more prevalent. Yet nowadays, restricting civic space is often exercised in the form of digital attacks and criminalization. Almas from ICW considers shrinking civic space as a real threat which endangers advocacy and lives. She added that shrinking civic space hinders the quality of life because it restricts the right to engage more meaningfully in the policymaking process, and to monitor the government and public services. Like many other countries in the region, Indonesia has had public information laws since 2008; but in reality, it is still hard for civil society to get information from the government. One may need to go to the Information Commission and engage in a lengthy process to finally get information from the government. Government action and initiative is necessary.

Strengthening networks is key

Almas from Indonesia Corruption Watch shared that besides strengthening digital security by using multi-step verification, civil society must strengthen communication and network with other organizations that deal with digital security and civic space at the national and the regional levels.

Civic space in law and in practice

Mukhtar Ahmad Ali, Executive Director of the Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives (CPDI), confirmed that constitutional guarantees for civic freedom exist in Pakistan. However, like many other countries in the Asia-Pacific region, there are challenges to the effective implementation of the legal framework formulated to strengthen the role of civil society, beyond legal limitations. In many cases, laws at the federal level are not applicable to all provinces. Furthermore, disputed territories where territorial jurisdiction is not clearly defined means that implementation varies. Mukhtar also shared that student unions, one of the major avenues for political education, are banned on the grounds of political party backups. Raising concerns about governance and human rights is not a welcome discussion.

Mukhtar emphasized that over the last four decades, there have been legal improvements in Pakistan. Laws exists which require government agencies to consult and receive feedback from civil society organizations and citizens. Regulatory bodies have been set up to approve petitions. However, when it comes to implementation, official attitudes do not reflect an adequate level of commitment. Any feedback received from CSOs is not given proper consideration.

CSO challenges and opportunities

Along with the key speakers, other participants of the regional meeting agreed on the challenges faced by CSOs such as lack of resources, technical capacity, and proactivity. Rights-based organizations that work on accountability issues are typically dependent on foreign funding. However, they are obstructed on grounds of cultural, religious, and security perspectives. Access to foreign funding also varies because if the funding is not available, rights-based organizations struggle to garner support for their areas of work, which may not be locally popular such as women’s rights issues. Similarly, there are challenges with having approval from government authorities. Delays in approvals obstruct CSOs from implementing projects efficiently.

Media organizations also face challenges. Countless journalists have suffered violence, arbitrary detentions and harassment by state security agencies, as well as alleged unlawful detentions and prosecutions. While corporate media continues to prioritize and promote its own interests, local and community-based or not-for-profit media remains weak and unsustainable, struggling with the financial sustainability of their operations. Digital media growth has been exponential, but is juggling its own constraints: capacity and sustainability. For more clicks and viewership, quality is compromised.

Despite the wide variety of challenges, there were mentions of the opportunities to be found in politically engaged youth groups who are vocal and active. They present opportunities for more dialogue and debate within society, which can enlighten citizens about how to engage and set them on a clearer advocacy path.

The regional meeting concluded on a hopeful note, encouraging the network to continue sharing and pooling efforts across the region. Participants are invited to use the UNCAC Coalition platform to raise their voices at the global level, by adding their inputs to the thematic policy papers being prepared for the upcoming CoSP10.