23 December 2022 –

An effective anti-corruption agency (ACA) is a great strength in the fight against corruption. The UNCAC provides specific provisions ensuring the existence of such a specialized body with legal and institutional capacities for the prevention of corruption, under Article 6.

The UNCAC Coalition’s 9th Regional Meeting of the Asia-Pacific Region was held virtually on 15 December 2022, focusing on Anti-Corruption agencies in the region. The meeting gathered Asia-Pacific members, affiliated groups and colleagues from the Coalition’s Vienna Hub. Fatema Afroz, Regional Coordinator for Asia-Pacific, opened the meeting, introducing the speakers and participants.

The meeting was kicked off with a few updates from Vienna. Denyse Degiorgio, Project Officer at the Vienna Hub, delivered messages about the UNCAC Coalition’s recent activities in UNCAC fora including observing international anti-corruption day, participating in the international anti-corruption conference, and the launch of the international database on legal standing for victims of corruption (VoC). Updates about ongoing projects, such as the ATI campaign, included a response from government authorities in Australia, with the successful release of official UNCAC documents. More updates were given about other tools of the Coalition including the UNCAC review status tracker, through which civil society can find out more about the review status in their country, and how to get involved. The regional meeting then zoomed in on the topic of anti-corruption agencies.

Anti-corruption Agencies – Which models work?

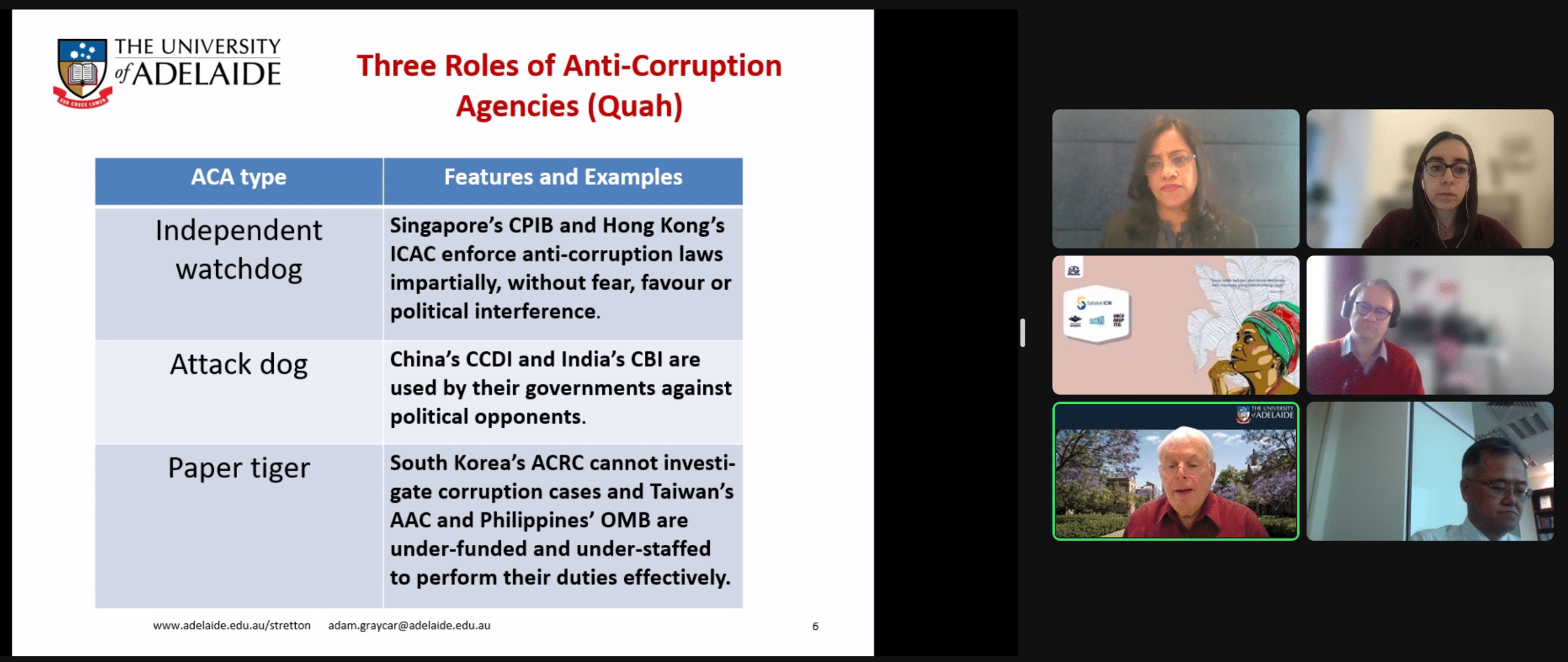

Adam Graycar, Professor of Public Policy and Director of Stretton Institute at the University of Adelaide, Australia, presented different models of anti-corruption agencies, along with details on Australia’s experience. He considered accountability as a fundamental principle, the absence of which results in corruption. The crucial role of anti-corruption agencies is well-accepted. However, he admitted that an ACA is not a ‘silver bullet’ that will solve every problem: agencies should identify where opportunity for them to work exists. In Australia, ACAs exist at state levels. However, a national agency has just been established, following commitments by the new government.

The necessity of an anti-corruption agency in Australia was not always agreed upon within government. In recent years, the country’s rating on the global Corruption Perception Index has deteriorated. Parliament’s new decision to restrict the scope of the ACA may result in a less effective agency, however, it is expected to be exempt from political interference. Simply establishing an anti-corruption agency does not solve corruption but rather, the agency’s nature determines its effectiveness against corruption. Different models of anti-corruption agencies, such as ‘watchdogs’, ‘attack dogs’, ‘paper tigers’ or ‘guard dogs’, can result in different levels of effectiveness. Professor Adam mentioned issues of push-back for successful agencies, suggesting that the anti-corruption body should not be the investigator and the judge simultaneously; but these two functions should be separated.

Learning from Indonesia: The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK)

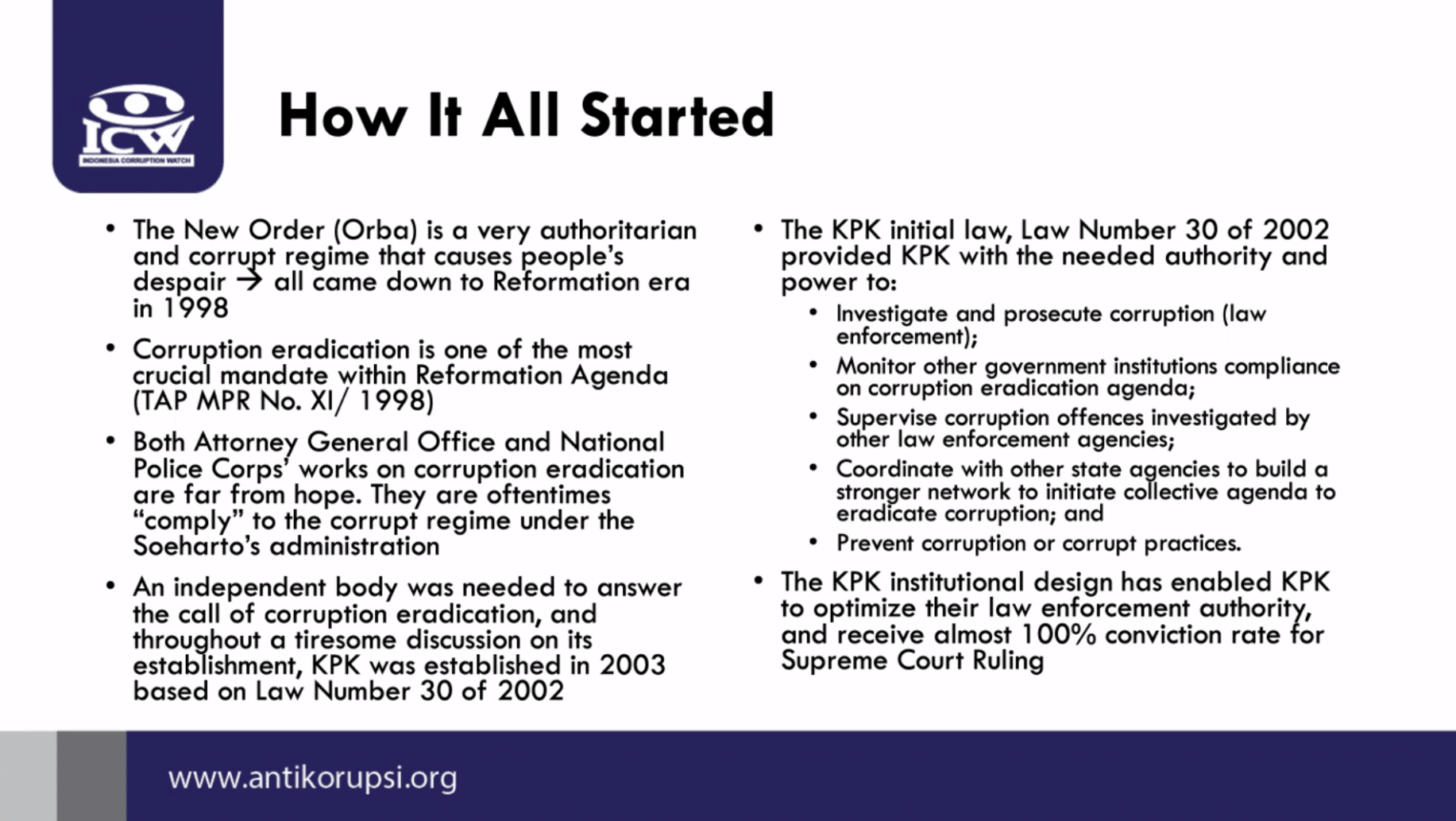

Lalola Easter from Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) presented insights from her country. The corruption eradication commission of Indonesia, known as the KPK (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi), was established in 2003. Since its establishment, KPK is known to be the most rigorous law enforcement institution for corruption investigation and prosecution in Indonesia. Along with the power to investigate and prosecute corruption, it is empowered to monitor government institutions’ compliance with anti-corruption, to supervise corruption offences investigated by other law enforcement agencies and to coordinate with other state agencies to build a stronger network and initiate a collective agenda on the eradication of corruption in the country.

Lalola Easter from Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) presented insights from her country. The corruption eradication commission of Indonesia, known as the KPK (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi), was established in 2003. Since its establishment, KPK is known to be the most rigorous law enforcement institution for corruption investigation and prosecution in Indonesia. Along with the power to investigate and prosecute corruption, it is empowered to monitor government institutions’ compliance with anti-corruption, to supervise corruption offences investigated by other law enforcement agencies and to coordinate with other state agencies to build a stronger network and initiate a collective agenda on the eradication of corruption in the country.

On the other hand, through their aggressive law enforcement work, the KPK is known to be hated by corrupt actors and their cronies, who started fighting back. There have been attempts to push back on their work by putting ‘problematic’ people in strategic positions. Between 2019-2020, the KPK faced restructuring that changed its whole existence, and marking the KPK’s decline. Up until mid-2019, the KPK had a collaborative relationship with civil society organizations. After the restructuring in October 2019, civil society participation was no longer taken into account.

Finally, Lalola presented five factors for an ACA to be effective. It should be:

- independent from government institutions;

- supported by a strong law;

- in possession of strong political support from the head of state and/or head of government;

- backed by strong public support; and

- engaged in a transparent and accountable selection process for the Commissioners.

The presentation was followed by an dynamic discussion that touched upon essential elements such as how democratic values, human rights and the anti-corruption fight go hand in hand. The meeting emphasized the necessity of civil society support to ensure that anti-corruption initiatives neither backslide nor become subject to misuse of entrusted power.