12 May 2022 –

Whistleblowers, alongside investigative journalists and civil society activists, play an essential role in exposing and tackling financial crimes and corruption. Not only do they safeguard, and sometimes help recover, misused public funds, but they also raise awareness about the devastating societal impacts of corruption, and contribute to bringing about policy reforms and a shift towards a culture of public accountability and integrity. The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) recognizes the importance of whistleblowers and provides a basis for national legal frameworks (especially through Articles 8 and 33).

Progress and setbacks of establishing effective whistleblowing systems and protection of whistleblowers was the topic chosen by the Europe network for its second regional meeting, held on Thursday 5th of May. Four speakers from Germany, the Czech Republic, North Macedonia and an international organization, as well as more than 20 participants reflected on the challenges to adopting comprehensive legislation in their countries, and shared advocacy strategies and initiatives they have put in place to advance whistleblower protection frameworks.

Progress and setbacks of establishing effective whistleblowing systems and protection of whistleblowers was the topic chosen by the Europe network for its second regional meeting, held on Thursday 5th of May. Four speakers from Germany, the Czech Republic, North Macedonia and an international organization, as well as more than 20 participants reflected on the challenges to adopting comprehensive legislation in their countries, and shared advocacy strategies and initiatives they have put in place to advance whistleblower protection frameworks.

The insights shared by members and affiliated groups were used to draft the Coalition statement on whistleblower protection to be presented to the UNCAC Implementation Review Group (IRG) meeting in June.

As legislation is being adopted across Europe, more transparency and participation is needed

The meeting began with an update from Danella Newman on the Coalition’s latest activities and a brief summary by Ana Revuelta of the responses provided by the membership in Europe to the Annual Activity Survey. The four speakers then took the floor.

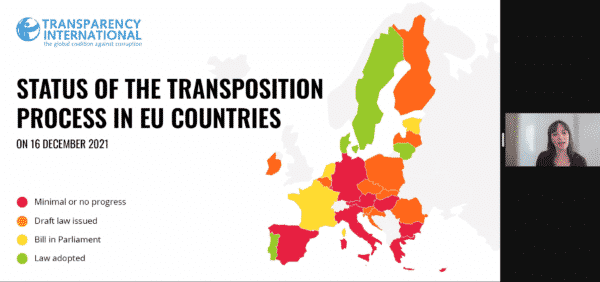

Marie Terracol, Whistleblower Protection Lead at Transparency International, focused on the European Union and gave an overview of how the EU Whistleblower Protection Directive is being transposed across the 27 EU member states.

In 2019, the European Union took a promising step with the adoption of the Whistleblower Protection Directive. Through ground-breaking provisions, a range of public and private organizations must establish reporting channels and any person reporting wrongdoing in the context of work-related activities shall be guaranteed legal protection and support, irrespectively of their motives. However, the situations considered in the Directive are insufficient. Governments need to go beyond the restrictive scope of the Directive (breaches of EU law in defined areas) if they are to offer effective protection to whistleblowers speaking up in the public interest.

Besides, the status of the transposition process in EU countries is lagging past the deadline – there are still 7 countries that have made minimal or no progress. As Marie explained, transposition does not only mean adopting a law, but bringing into force a set of laws, regulations and administrative provisions. Therefore, it is essential for civil society to be involved and keep advocating for stronger guarantees. Marie claimed that quality should go over speed: adopting a law is important but not at the cost of a transparent and inclusive process.

Besides, the status of the transposition process in EU countries is lagging past the deadline – there are still 7 countries that have made minimal or no progress. As Marie explained, transposition does not only mean adopting a law, but bringing into force a set of laws, regulations and administrative provisions. Therefore, it is essential for civil society to be involved and keep advocating for stronger guarantees. Marie claimed that quality should go over speed: adopting a law is important but not at the cost of a transparent and inclusive process.

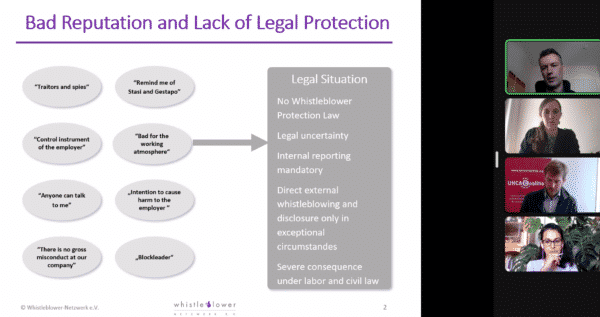

Citizen initiatives to change cultural perceptions and advocate for the sound protection of whistleblowers

Kosmas Zittel, Managing Director at Whistleblower-Netzwerk, regretted the bad reputation that whistleblowing still has in Germany, in part, for historical reasons. There is no whistleblower law in Germany to date, except some regulations in the financial sector and others. As a result, whistleblowers face legal uncertainty as to when it is allowed or not to blow the whistle. Employees can only report to their superior under certain circumstances, and to report outside of the organization, they have to prove the absence of internal reporting channels.

Kosmas Zittel, Managing Director at Whistleblower-Netzwerk, regretted the bad reputation that whistleblowing still has in Germany, in part, for historical reasons. There is no whistleblower law in Germany to date, except some regulations in the financial sector and others. As a result, whistleblowers face legal uncertainty as to when it is allowed or not to blow the whistle. Employees can only report to their superior under certain circumstances, and to report outside of the organization, they have to prove the absence of internal reporting channels.

When Whistleblower-Netzwerk was founded in 2006, they realized that to change the legal status of whistleblowers, they first had to change prejudices against them and highlight their importance. They started by sharing stories of whistleblowers online. Working in coalition with labor unions and other CSOs, and with the support of journalist associations and some political parties, they contributed to improving the reputation of whistleblowers.

Concerning the prospects of legislation in Germany, the bill recently proposed by the new government contains strengths and weaknesses. For instance, whistleblowing of gross misconduct that does not violate the law is not protected, financial support for whistleblowers is not foreseen and disclosure of classified information is only considered in exceptional circumstances. The latter two points are the main issues on which Whistleblower-Netzwerk will now focus its work.

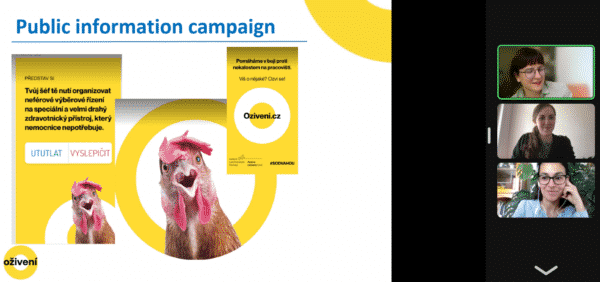

Šárka Zvěřina Trunkátová, President of Oživení and Coordinator of the “Whistleblower protection” project, spoke next and explained that the Czech Republic failed to meet the transposition deadline due to elections. As always happens in the country, the new government started a draft whistleblower law from scratch. Parliamentary approval should begin in autumn 2022, but Šárka regretted that there is no public debate on the law or on whistleblowing protection in the Czech Republic.

To counter this situation, Oživení launched a public opinion survey to measure awareness, as well as feelings and emotions regarding whistleblowing. The most important finding was that, if people understand what practices are wrong and their consequences for society, they are more willing to report on them. To raise awareness, the organization conducts campaigns including graphics and phrases for social media and encourages people to share experiences with whistleblowing in their workplace.

To counter this situation, Oživení launched a public opinion survey to measure awareness, as well as feelings and emotions regarding whistleblowing. The most important finding was that, if people understand what practices are wrong and their consequences for society, they are more willing to report on them. To raise awareness, the organization conducts campaigns including graphics and phrases for social media and encourages people to share experiences with whistleblowing in their workplace.

In terms of advocacy, Oživení are part of “Reconstruction of the State”, a platform for citizen lobbying through which they advocate, among other issues, for the recognition and protection of whistleblowers. They cooperate with other civil society organizations to present a common position and propose amendments to the whistleblower bill. Finally, they maintain good relations with officials from the Ministry of Justice involved in drafting the law.

The last presentation covered the very different scenario of North Macedonia, an EU candidate member with a law on whistleblower protection since 2016. The project of Transparency International Macedonia focused on implementation of this law and was presented by Aleksandra Blanusha, Project Assistant at TI Macedonia.

In North Macedonia, the law concerns three kinds of reporting: internal within organizations, external to public institutions such as the ombudsman, and public, where a person comes out publicly to the media. TI Macedonia seeks to achieve a proper implementation of the current whistleblower legislation, including further aligning it with the EU acquis. As the law obliges each public institution to appoint a specific person to ensure whistleblower protection, TI Macedonia created a website with a table listing public institutions and information of who to contact if you want to blow the whistle and ask for protection. The table now includes 151 contact details of public officials responsible for receiving reports from whistleblowers. They also produced a publication on the whistleblower law and disseminated it to 3000 institutions. In terms of awareness raising, TI Macedonia maintains an interactive platform available to any person who wants to blow the whistle.

In North Macedonia, the law concerns three kinds of reporting: internal within organizations, external to public institutions such as the ombudsman, and public, where a person comes out publicly to the media. TI Macedonia seeks to achieve a proper implementation of the current whistleblower legislation, including further aligning it with the EU acquis. As the law obliges each public institution to appoint a specific person to ensure whistleblower protection, TI Macedonia created a website with a table listing public institutions and information of who to contact if you want to blow the whistle and ask for protection. The table now includes 151 contact details of public officials responsible for receiving reports from whistleblowers. They also produced a publication on the whistleblower law and disseminated it to 3000 institutions. In terms of awareness raising, TI Macedonia maintains an interactive platform available to any person who wants to blow the whistle.

Discussion on what comprehensive legislation is and what civil society can do

A stimulating discussion followed the presentation on the quality of legislation and frameworks to protect whistleblowers, and what we can do, from a civil society perspective, to advocate for good legislation and sound enforcement.

A first point was made around whistleblowing on corruption, as the EU Directive only refers to offenses to EU law. For example, cases of whistleblowing on public procurement are not covered because they relate to national law. A second point was made on the difficulties to implement and sustain the protection of whistleblowers in time. In high-level corruption cases, whistleblowers may be at the mercy of political changes and end up being investigated themselves and their identities revealed in the public sphere. In other cases, whistleblowers are dragged to court as they were sued by their employers.

The transposition of the EU Directive presents risks and opportunities. For example, allowing for anonymous reporting and expanding the scope of protection would be positive trends, but they might in turn increase the number of exemptions at the national level, like the amount of classified information on which it is not allowed to blow the whistle. One issue we need to keep in mind is that the “over institutionalization” of whistleblower protection can create bottlenecks for reporting. However, since things are not yet tied up in many countries, civil society organizations can monitor the adoption of legislation and submit recommendations to the government and parliament, both on the process to demand for transparency and participation, and on the content of the legislation.

Finally, the discussion raised the point that whistleblowing can be about everything. It brings an opportunity for civil society to cooperate beyond the anti-corruption agenda and reach out to other actors, for example, on issues related to the environment. Cooperation within civil society has proven impactful in countries where there were risks of legislation being watered down in the adoption process, and a solid coalition of organizations has advocated for the highest standards to be maintained.